Have some fun with .net core startup hooks

One feature of .net core 2.2 that didn’t catch my attention immediately is the startup hooks. Put simply, this is a way to register globally a method in an assembly that will be executed whenever a .net core application is started. This unlocks a whole range of scenarios, from injecting a profiler to tweaking a static context in a given environment.

How does it work? First, you need to create a new .net core assembly, and add a StartupHook class. Make sure that it’s outside of any namespace. That class must define a static Initialize method. That’s the method that will be called whenever a .net core application is started.

The following hook, for instance, will display “Hello world!” when an application is launched:

using System;

internal class StartupHook

{

public static void Initialize()

{

Console.WriteLine("Hello world!");

}

}

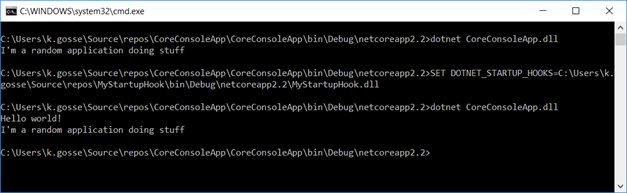

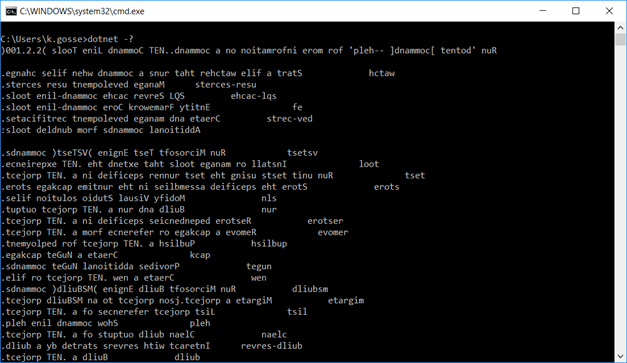

To register the hook, you need to declare a DOTNET_STARTUP_HOOKS environment variable, pointing to the assembly. Once you’ve done that, you’ll see the message displayed:

It’s really important to understand that the hook is executed inside of the application process. And a globally registered hook that runs inside of all .net core processes sounds like a good prank setup for unsuspecting coworkers.

The inverted console

What kind of prank? Let’s start with something simple: what about overriding the console stream to reverse the displayed text? First we write a custom TextWriter:

public class InvertedTextWriter : TextWriter

{

private readonly TextWriter _writer;

public InvertedTextWriter(TextWriter baseTextWriter)

{

_writer = baseTextWriter;

}

public override Encoding Encoding => _writer.Encoding;

public override void Write(string value)

{

_writer.Write(string.Concat(value.Reverse()));

}

}

Then we assign it to the console in the startup hook:

internal class StartupHook

{

public static void Initialize()

{

Console.SetOut(new InvertedTextWriter(Console.Out));

}

}

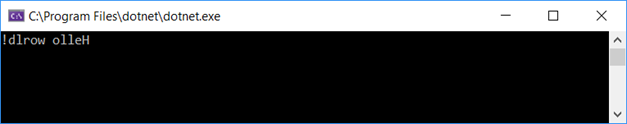

Once the startup hook is registered, all .net core 2.2 applications will output inverted text in the console:

And the best part is that it even works for the “dotnet.exe” executable itself!

You can easily imagine the confusion that would come from it.

Overriding Array.Empty

Is there anything else we can do? I’ve been unsuccessful at replacing the value of string.Empty (probably because it’s declared as an intrinsic), but we can instead replace the value of Array.Empty<T>. For instance for Array.Empty<string>:

internal class StartupHook

{

public static void Initialize()

{

var type = Type.GetType("System.Array+EmptyArray`1");

var arrayStringType = type.MakeGenericType(typeof(string));

var field = arrayStringType.GetField("Value", System.Reflection.BindingFlags.Static | System.Reflection.BindingFlags.NonPublic);

field.SetValue(null, new string[] { "Hello world!" });

}

}

This sounds rather inoffensive, until you consider the case of methods with params argument. For instance, this method:

public void PrintArgs(params string[] args)

{

foreach (var arg in args)

{

Console.WriteLine(arg);

}

}

From a C# point of view, you can call it without any parameter (PrintArgs()). But from an IL perspective, the args parameter is just an ordinary array. The magic is done by the compiler, which automatically inserts an empty array, effectively rewriting the call to PrintArgs(Array.Empty<string>()). Therefore, with the startup hook registered, the method called without any parameter will actually display “Hello world!”.

The async state machine

Those are already nice ways to confuse coworkers, but I wanted to go even farther. That’s when I thought of replacing the default TaskScheduler. What could we do with it? What about… rewriting values at random in the async state machine? When a method uses async/await, it is converted to a state machine that stores among other things the local variables used by the method (to restore the context when the await continuation starts executing). If we manage to retrieve that state machine, we can therefore change the value of the locals between each await!

We start by declaring our custom task scheduler (and name it ThreadPoolTaskScheduler in case somebody would think of inspecting the callstack), and we use it to overwrite TaskScheduler.Default.

internal class StartupHook

{

public static void Initialize()

{

typeof(Task).GetField("s_asyncDebuggingEnabled", BindingFlags.Static | BindingFlags.NonPublic)

.SetValue(null, true);

typeof(TaskScheduler).GetField("s_defaultTaskScheduler", BindingFlags.Static | BindingFlags.NonPublic)

.SetValue(null, new ThreadPoolTaskScheduler());

}

[DebuggerDisplay("ThreadPoolTaskScheduler")]

class ThreadPoolTaskScheduler : TaskScheduler

{

protected override IEnumerable<Task> GetScheduledTasks()

{

throw new NotImplementedException();

}

protected override void QueueTask(Task task)

{

MutateState(task);

ThreadPool.UnsafeQueueUserWorkItem(t => TryExecuteTask((Task)t), task);

}

private void MutateState(Task task)

{

// TODO

}

protected override bool TryExecuteTaskInline(Task task, bool taskWasPreviouslyQueued)

{

MutateState(task);

return TryExecuteTask(task);

}

}

}

Note that we also always set s_asyncDebuggingEnabled to true to avoid having a different behavior when the debugger is attached, which would complicate our code. The task scheduler calls an empty MutateState method, then uses the threadpool to schedule the task execution. Now we need to implement that method.

How to retrieve the state machine? The first step is to retrieve the ContinuationWrapper. This is a structure that wraps the task action when s_asyncDebuggingEnabled is set to true. Depending on the type of task, we can find it either on task action or on the state:

private void MutateState(Task task)

{

var continuationWrapperType = Type.GetType("System.Runtime.CompilerServices.AsyncMethodBuilderCore+ContinuationWrapper");

var taskAction = typeof(Task).GetField("m_action", BindingFlags.Instance | BindingFlags.NonPublic)

.GetValue(task);

Delegate func = task.AsyncState as Delegate ?? taskAction as Delegate;

if (func?.Target?.GetType() == continuationWrapperType)

{

var continuationWrapper = func.Target;

}

}

From there, we retrieve the value of the _continuation field and check if it is an instance of AsyncStateMachineBox. If it is, then we can find the state machine in the StateMachine field:

var continuationWrapper = func.Target;

var continuation = continuationWrapper.GetType().GetField("_continuation", BindingFlags.Instance | BindingFlags.NonPublic)

.GetValue(continuationWrapper) as Action;

if (continuation != null)

{

var asyncStateMachineBox = continuation.Target;

var stateMachineField = asyncStateMachineBox?.GetType().GetField("StateMachine");

if (stateMachineField != null)

{

var stateMachine = stateMachineField.GetValue(asyncStateMachineBox);

}

}

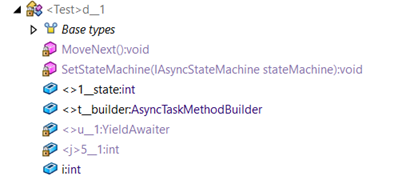

What does an async state machine look like?

Two public fields are always there: <>1__state and <>t__builder. <>1__state is used to store the current execution step in the async method. We could use it for instance to rewind the execution of the method. <>t__builder contains the facilities used to await other methods (nested calls). There’s plenty of stuff we could do with it, but we’ll focus on the locals.

The locals are stored in the private fields. In this case, <>u__1 and <j>5__1. Those are the ones we want to play with:

var stateMachine = stateMachineField.GetValue(asyncStateMachineBox);

var newStateMachine = Activator.CreateInstance(stateMachine.GetType());

foreach (var field in stateMachine.GetType().GetFields(BindingFlags.Instance | BindingFlags.NonPublic | BindingFlags.Public))

{

if (field.IsPrivate && field.FieldType == typeof(int))

{

field.SetValue(newStateMachine, _rnd.Next());

}

else

{

field.SetValue(newStateMachine, field.GetValue(stateMachine));

}

}

stateMachineField.SetValue(asyncStateMachineBox, newStateMachine);

What we do here is creating a new state machine, then copy the value of the old fields to the new ones. If the field is private and is an int, we replace it by a random value.

Now let’s make a simple program to test the hook:

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

Task.Run(Test);

Console.ReadLine();

}

static async Task Test()

{

int i = 42;

await Task.Delay(1000);

Console.WriteLine(i);

}

}

And you’ll see that… it doesn’t work. Why? Because the TPL has been pretty well optimized. In a lot of places, the code checks the current scheduler, and completely bypasses it if it’s the default one to directly schedule the continuation on the threadpool. For instance, in the YieldAwaiter (used by Task.Yield).

How can we work around that? We absolutely need our custom task scheduler to be the default one, otherwise it won’t be used when calling Task.Run. But if the default task scheduler is assigned to a task, then we won’t be called back and we won’t be able to mutate the state. If we check the code of the YieldAwaiter above, we can see that it’s doing a simple reference comparison. So we can overwrite the scheduler of the task with a new instance of our custom scheduler to fool those checks:

protected override void QueueTask(Task task)

{

MutateState(task);

var newScheduler = new ThreadPoolTaskScheduler();

typeof(Task).GetField("m_taskScheduler", BindingFlags.Instance | BindingFlags.NonPublic)

.SetValue(task, newScheduler);

ThreadPool.UnsafeQueueUserWorkItem(t => newScheduler.ExecuteTask((Task)t), task);

}

private void ExecuteTask(Task t)

{

TryExecuteTask(t);

}

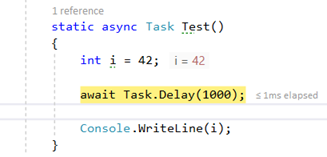

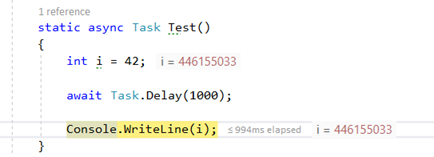

Are we done? If we go back to our example, we can start debugging step by step:

i is 42, all good. One more step and…

Now go and enjoy the dumbfounded looks of your coworkers!

Note that this won’t work when using ConfigureAwait(false), because it directly enqueues the continuation to the threadpool and won’t even check the current task scheduler (why would it?). One way around that could be to override the task builder with a custom one, but the joke already went far enough as is 🙂

Of course, all those tricks could have unpredictable effects on the target applications, so make sure to closely supervise the prank and stop as soon as it could become dangerous.