Why function pointers can't be used on instance methods in C#

A few days ago, a github issue in the dotnet/runtime repository piqued my interest. To summarize, the author was wondering why their code wasn’t working as expected. Here is a simplified version:

public unsafe class Getter

{

private delegate*<Obj, SomeStruct> _functionPointer;

public Getter(string propName)

{

var methodInfo = typeof(Obj).GetProperty(propName).GetGetMethod();

_functionPointer = (delegate*<Obj, SomeStruct>)methodInfo.MethodHandle.GetFunctionPointer();

}

public SomeStruct GetFromFunctionPointer(Obj target)

{

var v = _functionPointer(target);

return v;

}

}

public struct SomeStruct

{

public int Value1;

public int Value2;

public int Value3;

public int Value4;

}

public class Obj

{

public SomeStruct Property { get; set; }

}

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

var obj = new Obj { Property = new SomeStruct { Value1 = 42 } };

var getter = new Getter("Property");

Console.WriteLine($"Value: {getter.GetFromFunctionPointer(obj).Value1}");

}

}

Early diagnostic

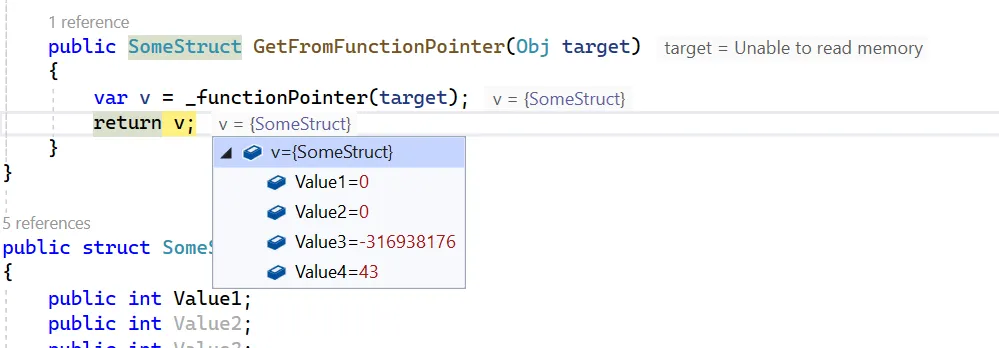

First, what are we looking at? The class Getter retrieves the getter of a property by reflection, then gets a function pointer to it, presumably to be able to invoke it without any performance penalty. When running the code, it displays Value: 0 even though the value should be equal to 42. Even more surprising, when running with a debugger, we can see that after invoking the function pointer, we can’t read the value of target anymore and v is filled with garbage:

So what’s going on?

The issue author noted that it worked when replacing SomeStruct with a reference type instead of a struct, and also when using a delegate instead of a function pointer (with methodInfo.CreateDelegate<Func<Obj, SomeStruct>>()). So at least we know it has something to do with value types, and that the function pointer is the culprit. The fact that target suddenly becomes invalid is a good hint that we have some kind of stack corruption.

When I tried to reproduce the issue, I initially couldn’t. Because the issue author didn’t provide the full code, I first tried with the simplest of structs:

public struct SomeStruct

{

public int Value1;

}

It worked flawlessly. Then I tried with a bigger struct and managed to reproduce the issue. After some trial and error, I concluded that the issue started to happen when the struct was bigger than 8 bytes. Also, if you look back at the screenshot from Visual Studio, you will see that Value1 and Value2 are equal to 0, and the garbage starts to appear with Value3. Given that the fields are of type int(4 bytes), it means that the garbage starts appearing after 2 x 4 = 8 bytes. What’s so special about 8 bytes? As the application is running in x64, this is the size of a pointer. Or of a register.

Piecing everything together

I then checked the specification of the function pointers. Among other things, it states that to be callable through a function pointer, a managed method has to be static. And indeed, it worked if I declared the property as static (and updated the signature of the function pointer accordingly). It means that the code is expected to fail, because function pointers can’t be used with instance methods. But it doesn’t really explain why, so I decided to dig further.

To understand what’s happening, we need to talk a bit about calling conventions and about the CLR ABI.

Note: the following explanations are written with x64 architecture in mind. There are a lot of differences in x86 or ARM

Most of the time, a function will have some arguments and/or a return value. For this to work, the caller and the callee have to agree on a convention to store and retrieve those values. This is called a calling convention, and is part of the ABI (Application Binary Interface).

There are many different calling conventions, but most of them are similar and try as much as possible to store the function arguments in registers, for performance reasons. The calling convention used by .NET for managed methods is no exception.

However this is not always possible. When the argument of a method is a struct with a size of 8 bytes or less, it fits nicely in a register. When it’s bigger, the caller will instead make a copy of the struct in a region of memory and store a pointer to that region of memory in the register. It means that structs are not passed by value strictly speaking, but a copy is made and this copy is passed by reference. Of course, from a C# perspective the end result is the same. The region of memory is usually allocated on the stack, though the specification explicitly allows to use the heap if appropriate.

There is an additional challenge for methods that return large structs. Just like for arguments, the struct won’t fit in a register so the callee will have to copy it to a region of memory and return a pointer. But where to allocate that memory? While it’s theoretically possible to use the stack, like the caller does, it is not great because the callee is supposed to restore the stack to its initial state when returning. It would be possible to use the heap, but this allocation would have a performance impact.

Instead, what happens is that the caller will reserve enough memory on the stack and give a pointer to that region of memory to the callee as an extra, hidden argument. Before returning, the callee will copy the struct to that region of memory and return its location. This is called a return buffer.

You may start to see why the function pointer may not work on non-static methods, but there is one last missing piece to have the complete picture: hidden arguments. There are many cases where a method may have hidden arguments (= arguments that are not explicit in the C# code, but that the method expects nonetheless). We won’t cover them all, but two hidden arguments are involved in our case:

-

The

thisargument. Whenever calling an instance method, there is a hidden argument to store the pointer to the instance -

The pointer to the return buffer

Those hidden arguments are provided in the order I mentioned them. It means that whenever calling a .NET method, the expected arguments are, in order:

-

The

thisargument (if the method isn’t static) -

The pointer to the return buffer (if needed)

Note that most calling conventions used by other languages expect those arguments in the reverse order (the pointer to the return buffer, then the this argument). The order picked by the CLR has one unfortunate side-effect. Indeed, let’s look at those two methods:

public class MyClass

{

public static LargeStruct StaticMethod(MyClass obj)

{

// ...

}

public LargeStruct InstanceMethod()

{

// ...

}

}

The expected arguments for those methods are:

StaticMethod:

-

The pointer to the return buffer, to store the return value

-

obj

InstanceMethod:

-

obj(as the hiddenthisargument) -

The pointer to the return buffer, to store the return value

The consequence is that it is not possible to reliably call a .NET method without knowing if it’s an instance or a static method. And the function pointers specification does not provide (yet?) a way to convey this information. When invoking a delegate* <MyClass, LargeStruct>, because the function pointer assumes that the target function is a static method, it will give the return buffer as the first argument, whereas an instance method would expect it as the second argument. This is why we end up corrupting the memory in our Getter class.

Going further

Just for the sake of it, to demonstrate that we properly understand the issue, we can try invoking our property getter with a function pointer by providing the hidden arguments ourselves.

As a reminder, we were trying to invoke an instance property getter, which has the following signature:

public SomeStruct get_Property();

Accounting for the hidden arguments, the “real” signature of the method is:

public SomeStruct* get_Property(Obj instance, SomeStruct* returnBuffer);

This is something we can call with some unsafe code:

public unsafe class Getter

{

private delegate*<Obj, SomeStruct*, SomeStruct*> _functionPointer;

public Getter(string propName)

{

var methodInfo = typeof(Obj).GetProperty(propName).GetGetMethod();

_functionPointer = (delegate*<Obj, SomeStruct*, SomeStruct*>)methodInfo.MethodHandle.GetFunctionPointer();

}

public SomeStruct GetFromFunctionPointer(Obj target)

{

// Allocate some space on the stack for the return value

SomeStruct returnValue = default;

var v = _functionPointer(target, &returnValue);

// We get a pointer to the return value. Dereference it to return the actual value to the caller

return *v;

}

}

And this should work as expected. Of course, please do not actually use this code in production, and keep in mind that it will only work for x64 (x86 and ARM have different calling conventions).