Monitor GC stats with a startup hook

.NET core startup hooks is a feature I really like, and I had a lot of fun with it in the past. Still, I had yet to find a legitimate use for them, and the opportunity finally came a few days ago.

What are startup hooks?

Let’s start by a quick catch-up, for those who don’t know what startup hooks are. The feature was introduced with .net core 2.2, and allows to execute any arbitrary code in a .net process before the Main entry point has a chance to run. This is done by declaring a DOTNET_STARTUP_HOOKS environment variable, pointing to the assembly you want to inject. The target assembly must declare a StartupHook class outside of any namespace, with a static Initialize method. That method is the entry point of the hook.

My use-case

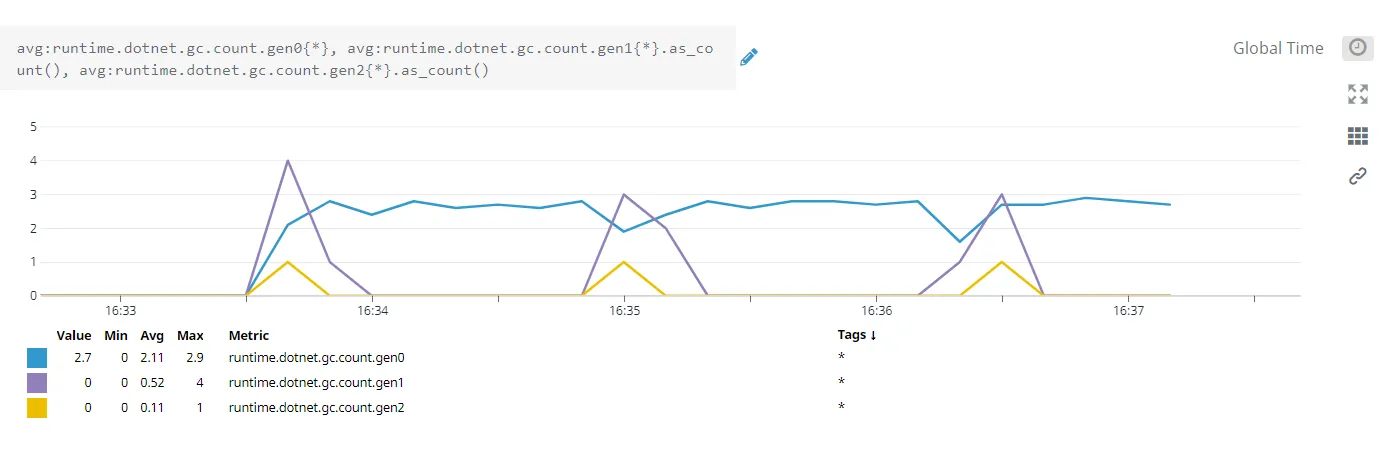

Back to the story. If you follow me on social medias, you might know that I joined Datadog a few weeks ago. I’m working on improving the performance of the .net tracer. As with any performance work, one of the first steps is to setup tests to measure the impact of the optimizations. Datadog already has a reliability environment, where the product is tested against popular applications, and key indicators are measured such as response time, CPU usage, or memory consumption. This was a very good start, but I also wanted to get stats about GC, and more precisely the number of garbage collections.

How to measure this? From inside of the process, it’s just a matter of calling GC.CollectionCount. From outside of the process it gets a bit trickier, as performance counters are not available for .net core applications. You can instead use ETW or event-pipes, as my former coworker Christophe Nasarre wrote back in the days. But this is quite a bit of work, and I was looking for a quick win. I needed an easy and unobtrusive way to inject my code inside of the applications we test. That’s when I remembered of startup hooks.

Using a startup hook to monitor GC collection count

The Datadog agent exposes a StatsD interface that can be used to push any arbitrary metric. My plan was to inject a thread in the target applications that would poll the number of collections and push it to the agent. Once you know about startup hooks, this is surprisingly straightforward to implement:

internal class StartupHook

{

public static void Initialize()

{

new Thread(PollGCMetrics)

{

IsBackground = true,

Name = "GCMetricsPoller"

}.Start();

}

private static void PollGCMetrics()

{

var dogstatsdConfig = new StatsdConfig

{

StatsdServerName = "127.0.0.1",

StatsdPort = 8125,

};

using var dogStatsdService = new DogStatsdService();

dogStatsdService.Configure(dogstatsdConfig);

while (true)

{

var gen0 = GC.CollectionCount(0);

var gen1 = GC.CollectionCount(1);

var gen2 = GC.CollectionCount(2);

dogStatsdService.Gauge("GC.Gen0", gen0);

dogStatsdService.Gauge("GC.Gen1", gen1);

dogStatsdService.Gauge("GC.Gen2", gen2);

Thread.Sleep(1000);

}

}

}

The code makes use of the DogStatsD-CSharp-Client nuget package. From there, it was just a matter of adding a DOTNET_STARTUP_HOOKS environment variable, pointing to the hook, to start monitoring any .net core application. Or so I thought.

The catch

Loading an arbitrary assembly intro a process that has no prior knowledge of it comes with (at least) one tricky part: handling references. My startup hook depended on the DogStatsD-CSharp-Client library, which itself had its own references, and all of those weren’t known to the target application at compilation time. This brought its fair share of dependency errors at runtime. Rather than trying to reconcile the errors on a case-per-case basis, I needed a way to isolate my dependencies from those of the target applications. .NET core does not support AppDomain, but brings a worthy successor: AssemblyLoadContext.

To take advantage of it, I separated my project into two assemblies: GCCollector, that starts the background thread and pushes the metrics, and GCStartupHook, which is the entry point of the startup hook. Inside, instead of directly referencing GCCollector, I load it through a dedicated AssemblyLoadContext, so that all of its dependencies are isolated:

public static void Initialize()

{

var loadContext = new StartupAssemblyLoadContext();

var assembly = loadContext.LoadFromAssemblyName(new AssemblyName("GCCollector"));

assembly.CreateInstance("GCCollector.Poller");

}

In the implementation of the AssemblyLoadContext, I needed to load all required dependencies. Rather than re-implementing the assembly resolve logic, I took advantage of new gem brought by .net core 3.0: AssemblyDependencyResolver.

The way it works is very straightforward. The resolver is given the path to an assembly, in this case GCStartupHook.dll. Whenever ResolveAssemblyToPath is called, it’s going to use the associated deps.json file in order to resolve dependencies just like if that assembly was a standalone application. Incredibly convenient for plugins… or for startup hooks.

class StartupAssemblyLoadContext : AssemblyLoadContext

{

private readonly AssemblyDependencyResolver _resolver;

public StartupAssemblyLoadContext()

{

_resolver = new AssemblyDependencyResolver(Assembly.GetExecutingAssembly().Location);

}

protected override Assembly Load(AssemblyName assemblyName)

{

string assemblyPath = _resolver.ResolveAssemblyToPath(assemblyName);

if (assemblyPath != null)

{

return LoadFromAssemblyPath(assemblyPath);

}

return null;

}

}

With that, the hook is complete. All is left is publishing it, setting the DOTNET_STARTUP_HOOKS environment, and the GC metrics are pushed to the agent!