SuppressGCTransition

While working on the second edition of the Pro .NET Memory Management book, I did some research on the SuppressGCTransition attribute introduced in .NET 5, and figured it would make a nice complimentary article.

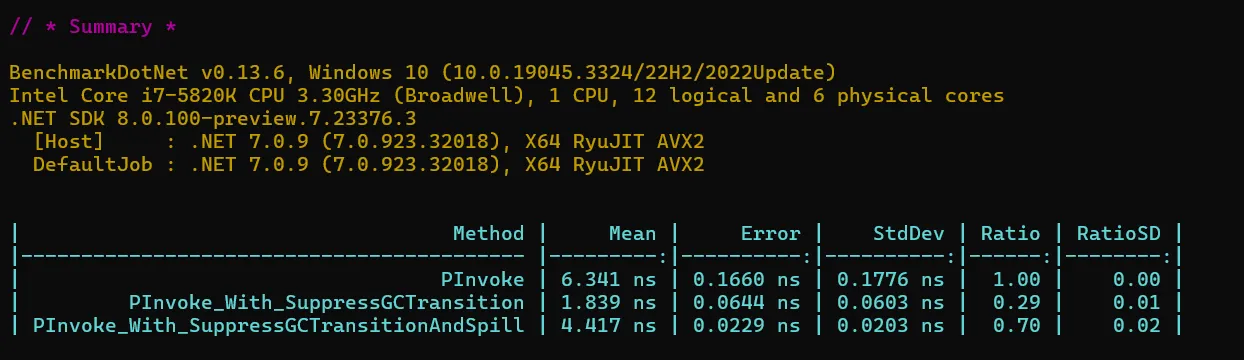

SuppressGCTransition is an attribute you can only apply on a method decorated with the DllImport attribute. It greatly reduces the overhead of the p/invoke, as illustrated with this benchmark:

public class SuppressGcTransitionBenchmark

{

[Benchmark(Baseline = true)]

public int PInvoke()

{

return Increment(42);

[DllImport("NativeLib.dll")]

static extern int Increment(int value);

}

[Benchmark]

public int PInvoke_With_SuppressGCTransition()

{

return Increment(42);

[DllImport("NativeLib.dll")]

[SuppressGCTransition]

static extern int Increment(int value);

}

}

As a side-note, I discovered when writing this code that you could declare p/invoke as local functions. It’s a great feature, since you often need to wrap your p/invokes in a managed function.

Increment is implemented in a native DLL, and simply increments the value of the argument:

extern "C" __declspec(dllexport) int32_t Increment(int32_t value)

{

return value + 1;

}

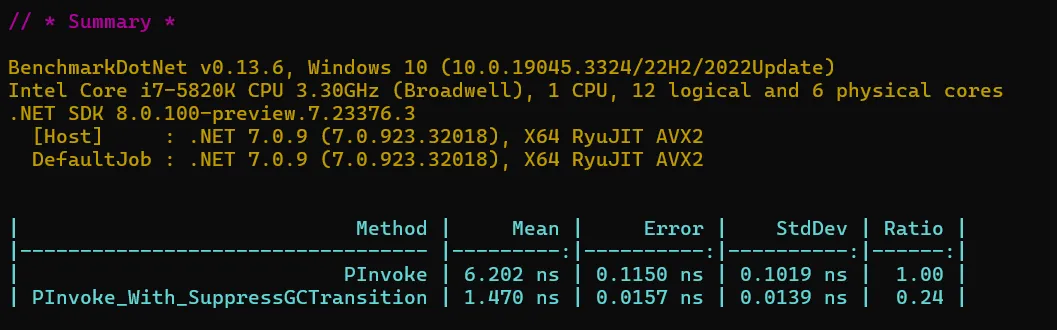

The results are impressive:

Just by adding the SuppressGCTransition attribute, the p/invoke was sped up by 4 times!

So, does it mean you should run to your codebase and add the magical attribute everywhere?

Well, not so fast.

What are the cons of SuppressGCTransition? There must be a catch...

— Stefán Jökull Sigurðarson (@stebets) August 11, 2023

As Stefán Jökull Sigurðarson cleverly pointed out in response to my bait, there has to be a catch, or .NET would just apply this optimization by default.

Consider this new benchmark:

public class SuppressGcTransitionBlockingBenchmark

{

private const int Length = 50_000;

private const int NumberOfTasks = 32;

[ParamsAllValues]

public bool SuppressGCTransition { get; set; }

[Benchmark]

public Task Concatenate()

{

var tasks = new Task<string>[NumberOfTasks];

for (int i = 0; i < NumberOfTasks; i++)

{

tasks[i] = Task.Factory.StartNew(() =>

{

var str = string.Empty;

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++)

{

var newStr = new string('c', Length);

var buffer = new char[str.Length + newStr.Length];

Concatenate(str, newStr, buffer);

str = new string(buffer);

}

return str;

}, TaskCreationOptions.LongRunning);

}

return Task.WhenAll(tasks);

}

private void Concatenate(string str1, string str2, char[] buffer)

{

if (SuppressGCTransition)

{

Concatenate_With_SuppressGCTransition(str1, str2, buffer);

}

else

{

Concatenate_Default(str1, str2, buffer);

}

}

[DllImport("NativeLib.dll", EntryPoint = "Concatenate")]

static extern void Concatenate_Default(string str1, string str2, char[] buffer);

[DllImport("NativeLib.dll", EntryPoint = "Concatenate")]

[SuppressGCTransition]

static extern void Concatenate_With_SuppressGCTransition(string str1, string str2, char[] buffer);

}

There’s a lot more going on here, let’s break it down. The Concatenate benchmark starts 32 threads. Each thread enters a loop where it will call the native Concatenate function 10 times to concatenate two strings into a char buffer, then convert it back to a string for the next iteration. Depending on the settings of the benchmark, the native Concatenate function will be called with or without SuppressGCTransition.

The native function is implemented as below:

extern "C" __declspec(dllexport) void Concatenate(WCHAR * str1, WCHAR * str2, WCHAR * output)

{

Sleep(100);

while (*str1 != '\0') {

*output = *str1;

output++;

str1++;

}

while (*str2 != '\0') {

*output = *str2;

output++;

str2++;

}

}

The function waits 100 ms, then concatenates the two strings into the char buffer.

This is of course a very dumb and inefficient way of concatenating strings, but I needed an example of code with the following characteristics:

-

Multiple threads

-

Lots of heap allocations

-

A native function that takes a significant amount of time to execute

While my example is not realistic, note that the vast majority of real world applications satisfy conditions 1 and 2.

Anyway, let’s run this benchmark and see what happens.

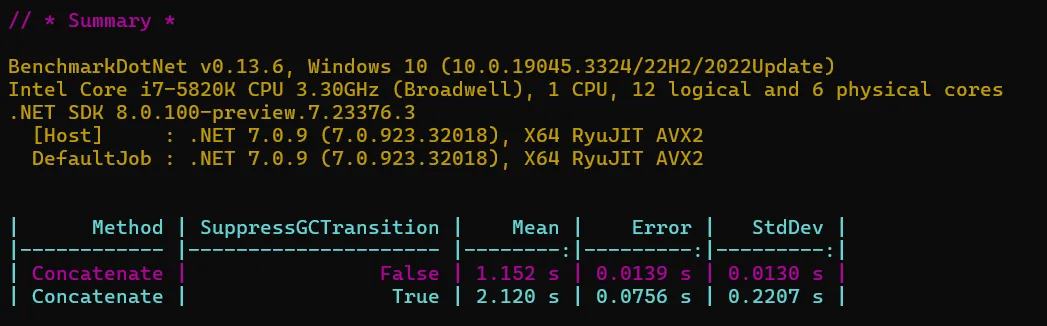

The benchmark gets almost twice as slow when SuppressGCTransition is enabled. How is that possible? Isn’t it supposed to magically speed up p/invokes?

To understand what’s going on, let’s first explain what the attribute is actually doing.

Preemptive GC vs cooperative GC

The main effect of SuppressGCTransition, when applied on a DllImport method, is to prevent the thread transition from cooperative GC mode to preemptive GC mode.

What are cooperative and preemptive mode? By default, .NET threads run in cooperative mode. When a collection is triggered, the garbage collector will try to suspend all cooperative threads, and make sure they’re stopped at a safe spot. The process is complex and described in this document. Note that if the thread is stopped at an unsafe spot, it will be immediately resumed and the GC will wait for it to suspend itself as soon as possible. Once all the threads are safely suspended, the GC can proceed with the collection.

But what about native code? How do you ask a native thread to suspend itself at a safe spot? The short answer is: you don’t. If you think about it, you don’t have to: suspension is needed for managed code because the GC might move memory and invalidate pointers. Native functions aren’t supposed to access managed memory (or only pinned objects that won’t be moved), so they’re not impacted by the garbage collector. Therefore, native threads run in preemptive mode, or “I don’t care about the GC” mode. The garbage collector will collect memory and move objects around without asking preemptive threads to be suspended.

To summarize, managed threads run in cooperative mode: they’re expected to cooperate with the GC to find a safe spot to stop when the GC wants to run a collection. Native threads run in preemptive mode: they can do whatever they want and the GC won’t wait for them before triggering a collection.

What about p/invokes? During p/invokes, a managed thread ends up executing native code, so it won’t be able to suspend itself if the GC needs to run. To allow the GC to run anyway, it switches itself to preemptive mode before executing the native code. When returning from the native call, it switches back to cooperative mode. But what if a collection was triggered while running the native method? The GC would have started moving memory without waiting for the p/invoke to exit (because the thread was in preemptive mode) and executing managed code would be unsafe. So before switching back to cooperative, the thread checks if a collection is in progress and immediately suspends itself if needed.

The term “GC transition” designates that moment when the thread switches to preemptive mode when executing a p/invoke, and switches back to cooperative mode at the end. One drawback is that it adds some overhead to the method call. The absolute cost is low (if you look at the benchmark at the beginning of the article, you will see that it’s just a few nanoseconds). However, if you call a native method that only does a trivial amount of computations (say for instance, reading a value from memory) then the relative overhead becomes significant (4 times slower in my benchmark). SuppressGCTransition has been introduced to allow you to suppress that overhead when it makes sense. It comes with a number of drawbacks. The main one is that no GC collection can run while a p/invoke decorated with SuppressGCTransition is running. That’s because the thread stays in cooperative mode, so the GC waits for it to suspend itself. If the p/invoke takes a significant amount of time to execute, as illustrated in my second benchmark, then all managed threads stop executing when a collection is triggered, and have to wait until that last thread finally suspends itself, which will only happen at the end of the native call. In the end, SuppressGCTransition is only safe to use when the cost of the native call is guaranteed to be smaller than the cost of the GC transition (that is, a few nanoseconds). Especially, it should never be applied on native calls that rely on I/Os or synchronization: even if they only take a few nanoseconds to execute in 99% of the cases, that one time when the I/O is delayed will have a dramatic impact on the performance of your application.

Effect on the debugger

The previous section should be enough to decide whether or not to use SuppressGCTransition in your code. But there’s an additional effect that I think is worth mentioning. When calling a native method, the runtime emits a Frame (with a capital F). The name is confusing, because despite being stored on the stack, a Frame is not a stack frame at the traditional sense. You can think of it as a cookie stored by the runtime to help unwind the stack if needed. You can read more on the subject in this excellent article written by Matt Warren.

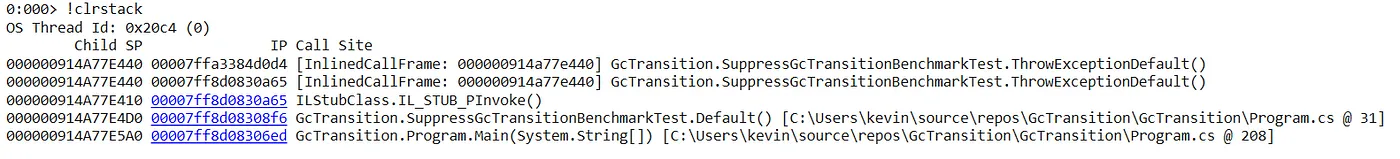

It might impact various aspects of the runtime (I’ll hide behind a cautious “I don’t know”), but what we’re interested in here is the impact on debuggers. Imagine you’re using a .NET debugger and trying to display the callstack of a managed thread currently executing a native call. The .NET debugger likely only knows how to unwind .NET code, so it will get confused by all the native stuff on top of the stack. To get around that, the debugger will retrieve the Frame and it will indicate where on the stack the managed code begins and ends. This way, the debugger can completely ignore the native part.

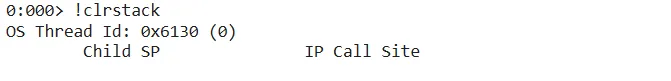

I don’t know if there is a technical reason, or if it’s just an effort to shave a bit more overhead (I assume so), but no Frame will be emitted when using SuppressGCTransition. The consequence is that the debugger doesn’t know where on the stack the managed code begins. It might get confused by the native stuff on top of the stack and fail to reconstruct the callstack.

I believe that’s a minor inconvenience: you should only use SuppressGCTransition on methods that are very fast, so the debugger is unlikely to stop on any of them. Still, that’s something to keep in mind.

The official documentation also mentions that the attribute shouldn’t be applied on native methods that may throw exceptions. I believe it has something to do with the absence of Frame, but I haven’t been able to produce any undesirable side-effect in my testing. You should still play safe and avoid any method that could throw an exception.

Reverse P/Invokes

The documentation also mentions that reverse p/invokes (when native code calls back into managed code) are forbidden when using SuppressGCTransition. I believe this is to avoid a situation where the thread remains stuck in preemptive mode. When a managed function is called from native code, the thread is expected to be in preemptive mode. Therefore, the method switches to cooperative mode at the beginning, then back to preemptive at the end. Now let’s see what happens if you have the following scenario:

managed code -> native code (p/invoke) -> managed code (reverse p/invoke)

First, when executing the managed code, the thread is in cooperative mode. Then, during the managed -> native transition, the thread doesn’t switch to preemptive because of the SuppressGCTransition attribute. Next, during the native -> managed transition, the thread stays in cooperative mode. Now, the reverse p/invoke exits so we work backwards. During the managed -> native transition, the thread switches to preemptive mode. Finally, during the last native -> managed transition, the thread stays in preemptive mode because of the SuppressGCTransition attribute. We end up with a managed thread that won’t pause during garbage collections! The situation is bad enough that the runtime emits a check at the beginning of the reverse p/invoke method, that will throw a fatal execution engine exception if it detects that the thread is already in cooperative mode.

Stack spill

While I was doing my research and tweeting previews of this article, Egor Bogatov pointed out another optimization done by SuppressGCTransition:

The problem that the 2nd pinvoke will inject a lot of codegen (basically, spill all regs) in your method's prolog even if you will be never using that path, I'd recommend to hide it under noinline method then.

— EgorBo (@EgorBo) July 31, 2023

I don’t exactly know why, but when a method has a p/invoke in one of its paths, a stack spill will occur. It means that the value of all registers is pushed on the stack. I believe it has something to do with the Frame that is also pushed on the stack. You can see that if you look at the assembly code of the method I used in the first benchmark:

push rbp

push r15

push r14

push r13

push r12

push rdi

push rsi

push rbx

sub rsp,78h

lea rbp,[rsp+0B0h]

mov qword ptr [rbp+10h],rcx

lea rcx,[rbp-88h]

mov rdx,r10

call coreclr!JIT_InitPInvokeFrame (00007ffd`85b7c0a0)

mov qword ptr [rbp-48h],rax

mov rcx,rsp

mov qword ptr [rbp-68h],rcx

mov rcx,rbp

mov qword ptr [rbp-58h],rcx

mov ecx,2Ah

mov rax,7FFD26219BB0h (MD: GcTransition.SuppressGcTransitionBenchmarkTest.Increment(Int32))

mov qword ptr [rbp-78h],rax

lea rax,[00007ffd`261207f8]

mov qword ptr [rbp-60h],rax

mov rax,qword ptr [rbp-48h]

lea rdx,[rbp-88h]

mov qword ptr [rax+10h],rdx

mov rax,qword ptr [rbp-48h]

mov byte ptr [rax+0Ch],0

call qword ptr [00007ffd`26219c58]

mov rdx,qword ptr [rbp-48h]

mov byte ptr [rdx+0Ch],1

cmp dword ptr [coreclr!g_TrapReturningThreads (00007ffd`85f62e74)],0

je 00007ffd`2612080f

call qword ptr [coreclr!hlpDynamicFuncTable+0xa8 (00007ffd`85f55378)] (JitHelp: CORINFO_HELP_STOP_FOR_GC)

mov rdx,qword ptr [rbp-48h]

mov rcx,qword ptr [rbp-80h]

mov qword ptr [rdx+10h],rcx

mov dword ptr [rbp-3Ch],eax

mov eax,dword ptr [rbp-3Ch]

add rsp,78h

pop rbx

pop rsi

pop rdi

pop r12

pop r13

pop r14

pop r15

pop rbp

ret

You can notice the 8 push instructions at the beginning of the method (and the matching 8 pop instructions at the end). When using SuppressGCTransition, the stack spill is gone:

push rbp

sub rsp,20h

lea rbp,[rsp+20h]

mov qword ptr [rbp+10h],rcx

call coreclr!JIT_PollGC (00007ffd`85c1d900)

mov ecx,2Ah

mov rax,offset NativeLib!Increment (00007ffe`2a8c1010)

call rax

nop

add rsp,20h

pop rbp

ret

That’s yet another reason why the overhead will be lower. In fact, the stack spill and the Frame seem responsible for most of the overhead, as demonstrated by this benchmark:

public class SuppressGcTransitionBenchmark

{

public bool Condition { get; set; }

[Benchmark(Baseline = true)]

public int PInvoke()

{

if (Condition)

{

return 1;

}

else

{

return Increment(42);

}

[DllImport("NativeLib.dll")]

static extern int Increment(int value);

}

[Benchmark]

public int PInvoke_With_SuppressGCTransition()

{

if (Condition)

{

return 1;

}

else

{

return Increment(42);

}

[DllImport("NativeLib.dll")]

[SuppressGCTransition]

static extern int Increment(int value);

}

[Benchmark]

public int PInvoke_With_SuppressGCTransitionAndSpill()

{

if (Condition)

{

// Will never get there

return Increment2(42);

}

else

{

return Increment(42);

}

[DllImport("NativeLib.dll")]

[SuppressGCTransition]

static extern int Increment(int value);

[DllImport("NativeLib.dll", EntryPoint = "Increment")]

static extern int Increment2(int value);

}

}

In PInvoke_With_SuppressGCTransitionAndSpill, I added a branch where a p/invoke without SuppressGCTransition is called. The branch is never executed, but that’s enough for the JIT to emit the Frame at the beginning of the method. The other methods are similar to the first benchmark except that I added the fake branch, just in case it has any impact on the performance.

In the results, we can see that PInvoke_With_SuppressGCTransitionAndSpill is significantly slower than PInvoke_With_SuppressGCTransition.

Summing it up

I hope you enjoyed this deep-dive into SuppressGCTransition. This is more knowledge than you need to safely use that attribute, so don’t worry if you got lost at some point. The documentation lists in a clear and concise way what to look for when using that attribute:

-

Native function always executes for a trivial amount of time (less than 1 microsecond).

-

Native function does not perform a blocking syscall (for example, any type of I/O).

-

Native function does not call back into the runtime (for example, Reverse P/Invoke).

-

Native function does not throw exceptions.

-

Native function does not manipulate locks or other concurrency primitives.

If your p/invoke meets all those points, then you can safely use the SuppressGCTransition attribute and enjoy the small (but free) performance gain.