Writing a .NET Garbage Collector in C# - Part 7: Marking handles

In the previous part of the series, we started implementing the mark phase and sweep phase of our garbage collector. I explained that roots are divided into three buckets: the local variables and thread-static storage, the GC handles, and the finalization queue. So far, we’ve only been scanning the first bucket. Now we’re going to scan the GC handles.

If you need a refresher, don’t hesitate to jump back to those past articles:

- Part 1: Introduction and setting up the project

- Part 2: Implementing a minimal GC

- Part 3: Using the DAC to inspect the managed objects

- Part 4: Walking the managed heap

- Part 5: Decoding the GCDesc to find the references of a managed object

- Part 6: Implementing the mark and sweep phases

Back in part 2, we used a simple fixed-size array to store the handles, noting that we would need to revisit this at some point. For our marking, we’re going to need to retrieve the handles by type, so this is a good time to implement a proper storage.

Revamping the handles store

Our handle store must meet a few requirements:

- Our storage must be capable of retrieving handles per type in an efficient way

- Once allocated, the address of a handle must never change. We could use pinned arrays, but I’d rather enforce this using native memory

- We need to be able to store an arbitrarily large number of handles

- The allocation of new handles must be thread-safe

The first requirement can be easily satisfied by creating one distinct store per handle type. For the next two requirements, we don’t have much choice: since we can’t reallocate our store (as this would force the handles to move in memory), we’re going to use a segment-based approach, where we allocate new segments as needed to accommodate the new allocations.

public unsafe class GCHandleStore

{

private readonly HandleSegmentList[] _lists;

public GCHandleStore()

{

// ...

// Allocate one list of segments per type of handle

_lists = new HandleSegmentList[HandleTypeCount];

for (int i = 0; i < HandleTypeCount; i++)

{

_lists[i] = new HandleSegmentList();

}

}

...

}

HandleSegmentList manages a linked list of HandleSegment. Because handles can be freed at any time, we implement a freelist to quickly find spare spots in a segment. We store the freelist information into the handles themselves. As a reminder, here is the structure of the handle:

[StructLayout(LayoutKind.Sequential)]

public unsafe ref struct ObjectHandle

{

public GCObject* Object;

public nint ExtraInfo;

public HandleType Type;

public void Clear()

{

Object = null;

ExtraInfo = 0;

}

}

That gives us plenty of space to work with. We add a dummy type of handle (HandleType.HNDTYPE_FREE), and we consider that whenever a handle is of type Free then the ExtraInfo field stores the index of the next free slot in the segment, if any.

public unsafe class HandleSegment

{

private readonly ObjectHandle* _buffer;

private readonly int _capacity;

private long _freeHead; // index of the first free slot, or -1

public HandleSegment? Next;

public HandleSegment(int capacity)

{

_capacity = capacity;

_buffer = (ObjectHandle*)NativeMemory.AllocZeroed((nuint)capacity, (nuint)sizeof(ObjectHandle));

// Build the freelist: each free slot's Type is HNDTYPE_FREE,

// and ExtraInfo holds the index of the next free slot.

for (int i = 0; i < capacity; i++)

{

_buffer[i].Type = HandleType.HNDTYPE_FREE;

_buffer[i].ExtraInfo = i + 1;

}

// -1 indicates that there is no free slot after this one

_buffer[capacity - 1].ExtraInfo = -1;

_freeHead = 0;

}

}

Then we implement a TryAllocate method, that tries to find a free slot in the segment. Because this might be called concurrently from multiple threads, we must make it thread-safe:

/// <summary>

/// Try to allocate a slot from this segment.

/// Returns null if the segment is full.

/// </summary>

public ObjectHandle* TryAllocate()

{

while (true)

{

var head = Volatile.Read(ref _freeHead);

if (head == -1)

{

return null;

}

var slot = _buffer + head;

var next = (int)slot->ExtraInfo;

if (Interlocked.CompareExchange(ref _freeHead, next, head) == head)

{

slot->Clear();

return slot;

}

}

}

Basically, we continuously try to replace the freelist head using atomic CAS (compare-and-swap) operations, until we either succeed or _freeHead becomes -1 (which would mean that somebody allocated the last free slot).

However, there’s a subtle race condition in this code, if we consider this scenario:

- Thread T1 reads

_freeHead = 5, and readsslot5->ExtraInfo = 6 - Thread T2 pops 5 (head is now 6), pops 6 (head is now 7), then pushes 5 back (head is now 5 again, but with

slot5->ExtraInfo = 7) - T1’s CAS succeeds (head is 5 again) and sets

_freeHeadto 6 (stale), losing node 7 and corrupting the chain

This is a scenario known as the ABA problem. The common fix is to pack a tag alonside the index, which allows to detect the case when the head has the same index but was actually popped and put back:

private static long Pack(int index, int tag) => ((long)tag << 32) | (uint)index;

private static (int Index, int Tag) Unpack(long packed) => ((int)(uint)packed, (int)(packed >> 32));

public ObjectHandle* TryAllocate()

{

while (true)

{

var packed = Volatile.Read(ref _freeHead);

var (head, tag) = Unpack(packed);

if (head == -1)

{

return null;

}

var slot = _buffer + head;

var next = (int)slot->ExtraInfo;

var newPacked = Pack(next, tag + 1);

if (Interlocked.CompareExchange(ref _freeHead, newPacked, packed) == packed)

{

slot->Clear();

return slot;

}

}

}

The Free method is similar, we try to replace the freelist head with our handle until we succeed:

/// <summary>

/// Return a slot to the freelist.

/// </summary>

public void Free(ObjectHandle* handle)

{

handle->Object = null;

handle->Type = HandleType.HNDTYPE_FREE;

var index = (int)(handle - _buffer);

while (true)

{

var packed = Volatile.Read(ref _freeHead);

var (head, tag) = Unpack(packed);

handle->ExtraInfo = head;

var newPacked = Pack(index, tag + 1);

if (Interlocked.CompareExchange(ref _freeHead, newPacked, packed) == packed)

{

return;

}

}

}

Back to our HandleSegmentList class, we keep track of the head and tail of our linked-list of HandleSegment:

public unsafe class HandleSegmentList

{

private const int SegmentCapacity = 256;

private readonly HandleSegment _head;

private HandleSegment _tail;

private readonly Lock _growLock = new();

public HandleSegmentList()

{

_head = new HandleSegment(SegmentCapacity);

_tail = _head;

}

}

The allocation code in HandleSegmentList is a bit more complex. We start by trying to allocate in the tail segment, as this is the most likely to succeed:

public ObjectHandle* Allocate()

{

// Fast path: try the tail segment (most common case)

var tail = Volatile.Read(ref _tail);

var result = tail.TryAllocate();

if (result != null)

{

return result;

}

}

If the tail segment is full, then we try every segment in the linked-list. There might be a faster way but for now we’re going to assume that the list of segments isn’t going to get too big:

// Scan all segments to find a free slot

var segment = _head;

while (segment != null)

{

result = segment.TryAllocate();

if (result != null)

{

return result;

}

segment = segment.Next;

}

If we didn’t manage to find a free segment, then we need to allocate a new one. While this part could be lock-free, we would need to optimistically allocate a chunk of memory and discard it if we lose the race. Without proper benchmarking, I’m going to assume this is counter-productive and we’re going to use some locking.

// Slow path: all segments are full, take a lock to grow

lock (_growLock)

{

// If tail changed, another thread already grew the list

if (tail != Volatile.Read(ref _tail))

{

continue;

}

// Still the same tail, append a new segment

var newSegment = new HandleSegment(SegmentCapacity);

// Allocate the handle *before* publishing the segment

// Otherwise there is a small risk that the segment gets full before we allocate

var handle = newSegment.TryAllocate()!;

Volatile.Write(ref tail.Next, newSegment);

Volatile.Write(ref _tail, newSegment);

return handle;

}

The whole thing is wrapped in a while loop, for the case when we lose the race while trying to acquire _growLock:

/// <summary>

/// Allocate a new handle in this list. Grows by adding a new segment if needed.

/// </summary>

public ObjectHandle* Allocate()

{

while (true)

{

// Fast path: try the tail segment (most common case)

var tail = Volatile.Read(ref _tail);

var result = tail.TryAllocate();

if (result != null)

{

return result;

}

// Scan all segments to find a free slot

var segment = _head;

while (segment != null)

{

result = segment.TryAllocate();

if (result != null)

{

return result;

}

segment = segment.Next;

}

// Slow path: all segments are full, take a lock to grow

lock (_growLock)

{

// If tail changed, another thread already grew the list

if (tail != Volatile.Read(ref _tail))

{

continue;

}

// Still the same tail, append a new segment

var newSegment = new HandleSegment(SegmentCapacity);

// Allocate the handle *before* publishing the segment

// Otherwise there is a small risk that the segment gets full before we allocate

var handle = newSegment.TryAllocate()!;

Volatile.Write(ref tail.Next, newSegment);

Volatile.Write(ref _tail, newSegment);

return handle;

}

}

}

The Free method is fortunately much easier. We never remove segments from the list, so we just have to check each segment until we find the right one:

/// <summary>

/// Free a handle that belongs to one of this list's segments.

/// </summary>

public void Free(ObjectHandle* handle)

{

var segment = FindSegment(handle);

segment?.Free(handle);

}

public HandleSegment? FindSegment(ObjectHandle* handle)

{

var segment = _head;

while (segment != null)

{

if (segment.ContainsHandle(handle))

{

return segment;

}

segment = segment.Next;

}

return null;

}

HandleSegment.ContainsHandle just checks that the given handle address is within its chunk of native memory:

public bool ContainsHandle(ObjectHandle* handle)

{

return handle >= _buffer && handle < _buffer + _capacity;

}

Last but not least, we implement an EnumerateHandlesOfType method on GCHandleStore which looks into the relevant store to enumerate all the allocated handles. I’m omitting the code of the enumerator for brevity, but you can check it directly on the GitHub repository.

public HandlesEnumerable EnumerateHandlesOfType(ReadOnlySpan<HandleType> handleTypes) => new(this, handleTypes);

Scanning the handles

Great, we can now go back to our mark phase. After part 6, our MarkPhase method looked like:

private void MarkPhase()

{

ScanContext scanContext = new();

scanContext.promotion = true;

scanContext._unused1 = GCHandle.ToIntPtr(_handle);

var scanRootsCallback = (delegate* unmanaged<GCObject**, ScanContext*, uint, void>)&ScanRootsCallback;

_gcToClr.GcScanRoots((IntPtr)scanRootsCallback, 2, 2, &scanContext);

}

After scanning the roots provided by the execution engine in GcScanRoots, we’re going to scan the strong handles. There are plenty of esoteric handle types in .NET, but fortunately most of them have been deprecated through the years. The only ones we need to care about now are HNDTYPE_STRONG (strong handles) and HNDTYPE_PINNED (pinned handles).

private void MarkPhase()

{

ScanContext scanContext = new();

scanContext.promotion = true;

scanContext._unused1 = GCHandle.ToIntPtr(_handle);

var scanRootsCallback = (delegate* unmanaged<GCObject**, ScanContext*, uint, void>)&ScanRootsCallback;

_gcToClr.GcScanRoots((IntPtr)scanRootsCallback, 2, 2, &scanContext);

ScanHandles();

}

private void ScanHandles()

{

ScanContext scanContext = default;

foreach (var handle in _gcHandleManager.Store.EnumerateHandlesOfType([HandleType.HNDTYPE_STRONG, HandleType.HNDTYPE_PINNED]))

{

var obj = handle->Object;

if (obj != null)

{

ScanRoots(obj, &scanContext, default);

}

}

}

This part was easy. Now, there is a more insidious type of handles to worry about: dependent handles. Dependent handles can be used either through the DependentHandle or the ConditionalWeakTable class. They allow to create a backward dependency between two objects.

For instance, consider two objects, A and B. If A references B (A --> B), then B will stay alive as long as A is alive. If we use a dependent handle (new DependentHandle(A, B)), we can get the same result but without having A reference B. This is very convenient, for instance, to attach properties to an object you don’t own. By using a dependent handle, you ensure that your property will automatically be freed when the target object is collected.

So why are dependent handles an issue for the GC? Because A keeps B alive without referencing it, we must first mark the heap and only then scan dependent handles:

private void MarkPhase()

{

ScanContext scanContext = new();

scanContext.promotion = true;

scanContext._unused1 = GCHandle.ToIntPtr(_handle);

var scanRootsCallback = (delegate* unmanaged<GCObject**, ScanContext*, uint, void>)&ScanRootsCallback;

_gcToClr.GcScanRoots((IntPtr)scanRootsCallback, 2, 2, &scanContext);

ScanHandles();

ScanDependentHandles();

}

private void ScanDependentHandles()

{

ScanContext scanContext = default;

foreach (var handle in _gcHandleManager.Store.EnumerateHandlesOfType([HandleType.HNDTYPE_DEPENDENT]))

{

// Target: primary

// Dependent: secondary

var primary = handle->Object;

var secondary = (GCObject*)handle->ExtraInfo;

if (primary == null || secondary == null)

{

continue;

}

if (primary->IsMarked() && !secondary->IsMarked())

{

ScanRoots(secondary, &scanContext, default);

}

}

}

However that’s not enough. Consider the following object graph:

A ··> B --> C ··> D

A keeps B alive through a dependent handle (symbolized as ··>). B keeps C alive through a direct reference (-->). C keeps D alive through another dependent handle. Let’s assume A is rooted somehow.

We start the marking phase and only find A. Then we scan the dependent handles and realize that A keeps B alive, so we continue the marking and find C. Great. But now C is marked, which means that we need to scan the dependent handles one more time to mark D, and so on!

So to properly scan the dependent handles, we must loop over the handles until we stop finding new objects to mark:

private void ScanDependentHandles()

{

bool markedObjects;

ScanContext scanContext = default;

do

{

markedObjects = false;

foreach (var handle in _gcHandleManager.Store.EnumerateHandlesOfType([HandleType.HNDTYPE_DEPENDENT]))

{

// Target: primary

// Dependent: secondary

var primary = handle->Object;

var secondary = (GCObject*)handle->ExtraInfo;

if (primary == null || secondary == null)

{

continue;

}

if (primary->IsMarked() && !secondary->IsMarked())

{

ScanRoots(secondary, &scanContext, default);

markedObjects = true;

}

}

}

while (markedObjects);

}

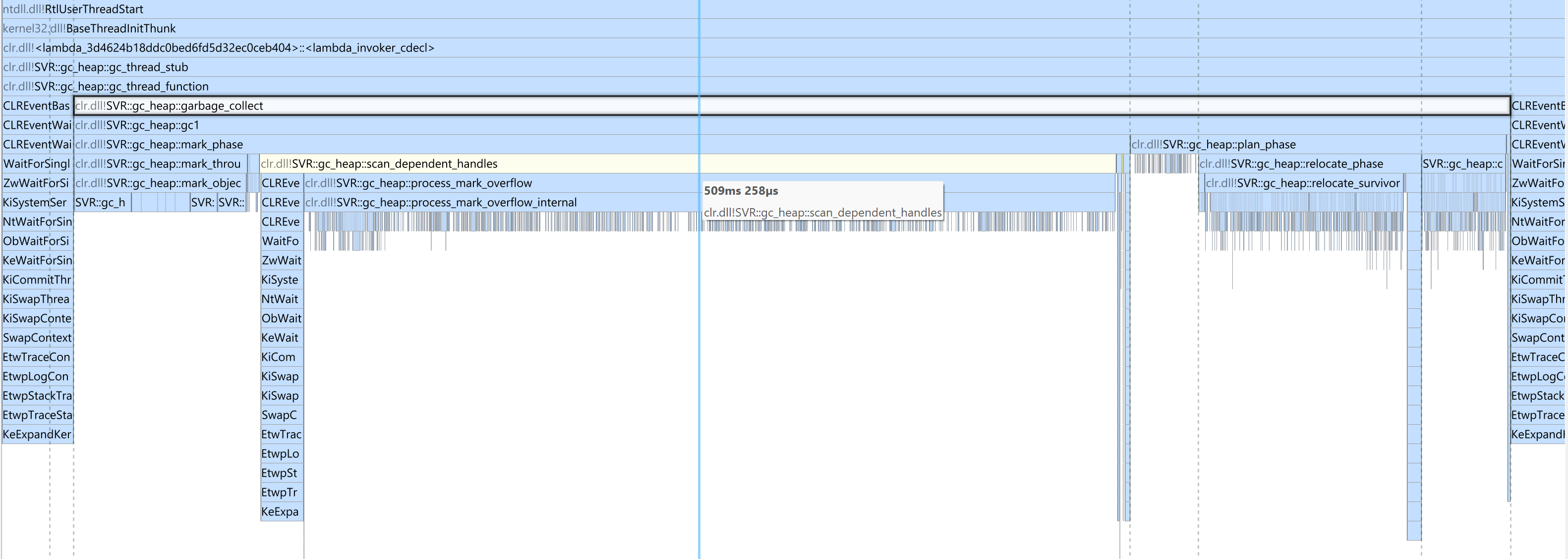

This part is actually a significant bottleneck in the .NET GC, so use dependent handles sparingly. To take a concrete example, I’ve observed in Visual Studio a 800 ms freeze during startup that was due to garbage collection. Upon further inspection, I discovered that during this collection the GC spends 60% of its time just scanning dependent handles!

ReSharper and Rider had the same issue when Solution-Wide Analysis was enabled, so we reworked our logic to reduce our reliance on dependent handles.

Clearing the handles

There is one more thing to do. After marking the heap, we must invalidate all the weak references and dependent handles that point to objects that weren’t marked. We do that during the sweep phase:

private void ClearHandles()

{

foreach (var handle in _gcHandleManager.Store.EnumerateHandlesOfType(

[HandleType.HNDTYPE_WEAK_SHORT, HandleType.HNDTYPE_WEAK_LONG, HandleType.HNDTYPE_DEPENDENT]))

{

var obj = handle->Object;

if (obj != null && !obj->IsMarked())

{

handle->Clear();

}

}

}

For now, we don’t differentiate short weak references and long weak references. The difference is that long weak references stay alive while an object is pending finalization, in case it gets resurrected. As we don’t support finalization yet, we don’t have to worry about it.

This is all for this part. At this point, our GC correctly manages weak references (assuming no finalization) and dependent handles, as demonstrated in those simple tests. Next time, we will have a look at interior pointers, last step before starting to implement finalization.

As usual, the full code is available on GitHub.