Exploring .NET frozen segments

.NET 8 introduced the concept of NonGC heap. It’s a special heap that, as the name indicates, is ignored by the GC. The runtime uses it to allocate objects that are guaranteed to stay alive forever (typically, string literals) and this allows the JIT to perform some neat optimizations (thanks to the guarantee that the object will never be moved). All of this is done automatically, without any knowledge of the developer. The only sign that something special is happening is if you try to check the generation of the object:

Console.WriteLine(GC.GetGeneration("Hello world!")); // 2147483647

The non-GC heap is built on top of frozen segments, a notion that has existed in the CLR for quite some time. There is a hidden, mostly experimental API that allows developers to create their own frozen segments and use them as they see fit. This will be the subject of this article.

Hidden for a good reason

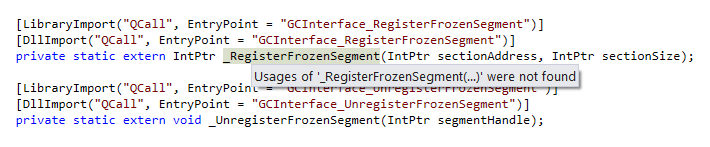

By “hidden”, I mean that this API is exposed by… private methods. As weird as it sounds, the GC._RegisterFrozenSegment and GC._UnregisterFrozenSegment methods are private and yet are intended for external usage, they’re never called by the base class library.

At the time of writing, UnsafeAccessor does not support static methods, so the only way to call those methods is through reflection:

internal static IntPtr RegisterFrozenSegment(IntPtr sectionAddress, nint sectionSize)

{

return (IntPtr)typeof(GC).GetMethod("_RegisterFrozenSegment", BindingFlags.NonPublic | BindingFlags.Static)!

.Invoke(null, [sectionAddress, sectionSize])!;

}

internal static void UnregisterFrozenSegment(IntPtr segment)

{

typeof(GC).GetMethod("_UnregisterFrozenSegment", BindingFlags.NonPublic | BindingFlags.Static)!

.Invoke(null, [segment]);

}

GC._RegisterFrozenSegment takes a pointer to a chunk of memory and its size, and registers it as a frozen segment. It returns a pointer to the internal bookeeping structure used to represent the segment. You only need it if you want to later call GC._UnregisterFrozenSegment.

Typically, you would first allocate a chunk of native memory with NativeMemory, then register it as frozen segment:

var size = 1024 * 1024 * 100; // 100 MB

var address = NativeMemory.AlignedAlloc((nuint)size, (nuint)IntPtr.Size);

NativeMemory.Clear(address, (nuint)size);

var segment = RegisterFrozenSegment((IntPtr)address, size);

Alright, we have our segment. What can we do with it? Frozen segments are the only supported way of storing managed reference objects into native memory. Why would you want to do that? Well, the only reason I can come up with is performance. The frozen segments are not scanned by the GC, so it can be a way to store large amounts of static data without impacting the application performance.

But how to allocate an object in the frozen segment? When calling the new allocator, there is no way to indicate where you want the object to be stored. Instead, you have to do everything… by hand. That’s right: partitioning the memory, writing the object header, calling the constructor… Everything. It will quickly become pretty obvious why the API is hidden, using it requires advanced knowledge of .NET data structures. Keeping the methods private is a way to make sure you know what you’re doing, or at least that you’re aware of the dangers. Think of the unsafe keyword, but unsafer.

Using the frozen segments

Allocating a string

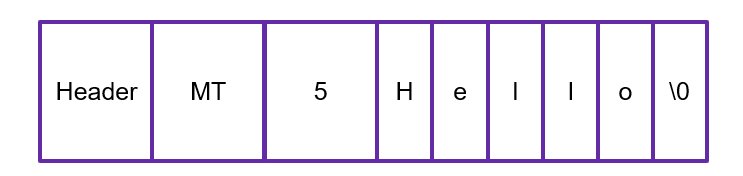

Let’s start “simple”: how to allocate a string in the frozen segment? First let’s have a look at the layout of a string:

Like every reference object, a string starts with a header, followed by a pointer to the method-table (MT). Then it contains the length, followed by every character and a null terminator (note that the length does not include the null terminator).

For the header, it’s easy, it’s going to be 0. Since we zero’d the native memory we don’t even need to assign it, but we’re still going to do it for clarity sake:

var size = 1024 * 1024 * 100; // 100 MB

var address = NativeMemory.AlignedAlloc((nuint)size, (nuint)IntPtr.Size);

NativeMemory.Clear(address, (nuint)size);

var segment = RegisterFrozenSegment((IntPtr)address, size);

var ptr = (byte*)address;

// Write the header

*(nint*)ptr = 0;

ptr += sizeof(nint);

Next is the pointer to the method-table. Fortunately there is an easy way to retrieve it in C#, even though it’s not documented as-is:

// Retrieve the method-table pointer

var mt = typeof(string).TypeHandle.Value;

// Write it

*(nint*)ptr = mt;

ptr += sizeof(nint);

Then comes the length:

*(int*)ptr = 5;

ptr += sizeof(int);

Finally, we write the characters and the null-terminator:

var dataPtr = (char*)ptr;

*dataPtr++ = 'H';

*dataPtr++ = 'e';

*dataPtr++ = 'l';

*dataPtr++ = 'l';

*dataPtr++ = 'o';

*dataPtr++ = '\0';

And that’s it! We have written our string in the frozen segment. To actually use it, we need to retrieve a reference to it. As a reminder, references in C# don’t point to the header but to the method-table pointer. So we take back our original address, increase it by the size of the header, and convert that to a string:

var strRef = (nint*)address + 1;

var str = *(string*)&strRef;

Console.WriteLine(str); // Hello

Let’s take a second to explain that code: first we store the address of the string in strRef. Then we take the address of strRef and reinterpret it as a pointer to a string. Finally, we dereference it to retrieve our instance of string.

We can wrap everything in a helper method:

static unsafe string AllocateString(void* address, ReadOnlySpan<char> data)

{

var ptr = (byte*)address;

// Write the header

*(nint*)ptr = 0;

ptr += sizeof(nint);

// Retrieve the method-table pointer

var mt = typeof(string).TypeHandle.Value;

// Write it

*(nint*)ptr = mt;

ptr += sizeof(nint);

*(int*)ptr = data.Length;

ptr += sizeof(int);

var destination = new Span<char>(ptr, data.Length + 1);

data.CopyTo(destination);

destination[^1] = '\0';

var strRef = (nint*)address + 1;

return *(string*)&strRef;

}

And we can call it like this:

var str = AllocateString(address, ['H', 'e', 'l', 'l', 'o']);

Console.WriteLine(str); // Hello

Allocating an array

Allocating an array is very similar. In fact, the layout of string is almost identical to an array. There are some crucial differences but we don’t care about them yet (ominous sound).

static unsafe T[] AllocateArray<T>(void* address, int length)

{

var ptr = (byte*)address;

// Write the header

*(nint*)ptr = 0;

ptr += sizeof(nint);

// Retrieve the method-table pointer

var mt = typeof(T[]).TypeHandle.Value;

// Write it

*(nint*)ptr = mt;

ptr += sizeof(nint);

// Write the length

*(int*)ptr = length;

var arrayRef = (nint*)address + 1;

// T[]* is not legal, so we need to cast to Array* first

return (T[])*(Array*)&arrayRef;

}

Then we can use it like an ordinary array:

var array = AllocateArray<int>(address, 5);

for (int i = 0; i < array.Length; i++)

{

array[i] = i;

}

Console.WriteLine(string.Join(',', array)); // 0, 1, 2, 3, 4

Allocating an object

Surely, after allocating a string an an array, allocating an object should be trivial? Well… sort of?

Allocating the object itself is indeed simpler than the other examples:

static unsafe T AllocateObject<T>(void* address) where T : class

{

var ptr = (byte*)address;

// Write the header

*(nint*)ptr = 0;

ptr += sizeof(nint);

// Retrieve the method-table pointer

var mt = typeof(T).TypeHandle.Value;

// Write it

*(nint*)ptr = mt;

var objRef = (nint*)address + 1;

return *(T*)&objRef;

}

Then we can use it like an ordinary object:

var obj = AllocateObject<MyObject>(address);

obj.Value = 1;

Console.WriteLine(obj.Value); // 1

However, what if the object has a non-default constructor?

public class MyObject

{

public int Value { get; set; } = 42;

}

The constructor is never called since we don’t use the new operator, and we end-up with an uninitialized object:

var obj = AllocateObject<MyObject>(address);

Console.WriteLine(obj.Value); // 0 if the memory is properly zero'd, otherwise... who knows

There are multiple ways to fix this problem. The easiest one is to use reflection to call the constructor:

var obj = AllocateObject<MyObject>(address);

var parameterlessConstructor = obj.GetType().GetConstructor([])!;

parameterlessConstructor.Invoke(obj, []);

Console.WriteLine(obj.Value); // 42

Another option is to use IL, for instance with InlineIL.Fody:

static unsafe void CallConstructor(MyObject obj)

{

IL.Emit.Ldarg_0();

IL.Emit.Call(new MethodRef(typeof(MyObject), ".ctor", []));

}

var obj = AllocateObject<MyObject>(address);

CallConstructor(obj);

Console.WriteLine(obj.Value); // 42

On the plus side, you avoid reflection (which forces you to box the constructor arguments, if any). On the minus side, you have to write a helper for each and every constructor (you can’t write a generic version of this code).

A good middle-ground is to retrieve the address of the constructor then cast it to a function pointer. It’s better than pure reflection because it avoids boxing the arguments, and it’s much more practical than using raw IL:

var obj = AllocateObject<MyObject>(address);

var constructorInfo = typeof(T).GetConstructor(Type.EmptyTypes);

// You should cache this if you need to call it multiple times

var ctor = (delegate*<MyObject, void>)constructorInfo.MethodHandle.GetFunctionPointer();

ctor(obj);

Allocating a struct

Allocating a struct is very similar to allocating an object, except that we don’t need to a header of the method-table pointer. We also want to return the struct by reference, otherwise we would end-up with a copy of the struct, defeating the purpose:

public ref T AllocateStruct<T>(void* address) where T : struct

{

var ptr = (byte*)address;

return ref Unsafe.AsRef<T>(ptr);

}

We have the same problem as before if we want to call the constructor. If you decide to use the function pointer approach, keep in mind that you need to pass the struct by reference:

ref var obj = ref AllocateStruct<MyStruct>(address);

var constructorInfo = typeof(T).GetConstructor(Type.EmptyTypes);

// You should cache this if you need to call it multiple times

var ctor = (delegate*<ref MyStruct, void>)constructorInfo.MethodHandle.GetFunctionPointer();

ctor(obj);

There is no GC where we’re going

As mentioned in the introduction, frozen segments are never scanned by the GC. A consequence that may not be immediately obvious is that any reference from a frozen segment to the managed heap is effectively a weak reference.

Consider the following example:

public class ObjectWithReferences

{

public object Reference;

}

[MethodImpl(MethodImplOptions.NoInlining)]

static WeakReference SetReference(ObjectWithReferences obj)

{

var target = new object();

obj.Reference = target;

return new WeakReference(target);

}

static unsafe AllocateInFrozenSegment(void* frozenSegmentAddress)

{

var obj = AllocateObject<ObjectWithReferences>(frozenSegmentAddress);

var weakReference = SetReference(obj);

GC.Collect();

Console.WriteLine(weakReference.IsAlive); // False

// Not actually needed since objects in the frozen segments are never collected,

// but just demonstrating the point

GC.KeepAlive(obj);

}

As you can see, the outgoing reference from the instance of ObjectWithReferences does not keep the target object alive.

Writing an allocator

Some readers may have noticed that so far, I’ve only ever allocated one object at a time. To allocate multiple objects, you have to know where the previous one ends so you can allocate the next one, and this is actually harder than it sounds. You might think “just call sizeof”, but unfortunately it’s not that easy.

Let’s take a concrete example:

public class MyObject

{

}

Console.WriteLine(sizeof(MyObject)); // 8

That actually sounds correct. Objects on the heap can’t be smaller than 3 pointers (24 bytes on 64-bit). So if we count 8 bytes for the header and 8 bytes for the MT pointer, that leaves 8 bytes of data, which could be what the sizeof operator returns.

Another example:

public class MyObject

{

public long data;

}

Console.WriteLine(sizeof(MyObject)); // 8

We have 8 bytes of data, sizeof(MyObject) returns 8, that’s still consistent.

Yet another example:

public class MyObject

{

public long data1;

public long data2;

}

Console.WriteLine(sizeof(MyObject)); // 8

Ok now this is definitely wrong. It turns out that calling sizeof on a reference returns the size of the reference (so IntPtr.Size), not the size of the referenced object.

sizeof won’t do the trick, we’re going to need something else.

Remember how we retrieved a pointer to the method-table earlier? The information we need is in that same table.

First, we declare a struct that mimics the layout of the method-table (only part of it, that thing is a mess):

[StructLayout(LayoutKind.Explicit)]

public struct MethodTable

{

[FieldOffset(0)]

public ushort ComponentSize;

[FieldOffset(4)]

public int BaseSize;

BaseSize is what we need, it contains the effective size of an object when stored on the heap. Let’s test it with our previous examples:

public class MyObject

{

}

var mt = typeof(MyObject).TypeHandle.Value;

var methodTable = *(MethodTable*)mt;

Console.WriteLine(methodTable.BaseSize); // 24

So far, so good. Remember, I explained that the minimum size of an object on the heap is 3 pointers, so 24 bytes on 64-bit.

public class MyObject

{

public long data;

}

var mt = typeof(MyObject).TypeHandle.Value;

var methodTable = *(MethodTable*)mt;

Console.WriteLine(methodTable.BaseSize); // 24

Still good: 8 bytes for the header, 8 bytes for the MT pointer, 8 bytes for the data.

public class MyObject

{

public long data1;

public int data2;

}

var mt = typeof(MyObject).TypeHandle.Value;

var methodTable = *(MethodTable*)mt;

Console.WriteLine(methodTable.BaseSize); // 32

Perfect: 8 bytes for the header, 8 bytes for the MT pointer, 12 bytes for the data, 4 bytes of padding.

Now we have everything we need to write an allocator! I’m too lazy to write a fully featured malloc with buckets and everything, so we will just write a simple bump-pointer allocator. Every time we allocate an object, we just bump the value of the pointer by the size of the object.

First, we layout the skeleton of our class:

public unsafe class BumpPointerNativeAllocator : IDisposable

{

private readonly IntPtr _segment;

private readonly long _limit;

private long _address;

public BumpPointerNativeAllocator(nint size)

{

_address = (IntPtr)NativeMemory.AlignedAlloc((nuint)size, 8);

NativeMemory.Clear((void*)_address, (nuint)size);

_segment = RegisterFrozenSegment((IntPtr)_address, size);

_limit = _address + size;

}

~BumpPointerNativeAllocator()

{

Dispose();

}

public void Dispose()

{

GC.SuppressFinalize(this);

UnregisterFrozenSegment(_segment);

NativeMemory.AlignedFree((void*)_address);

_address = 0;

}

}

Then we implement a private method to reserve a given amount of memory in a thread-safe way:

private nint* ReserveMemory(int size)

{

ObjectDisposedException.ThrowIf(_address == 0, typeof(BumpPointerNativeAllocator));

if (_address + size > _limit)

{

throw new OutOfMemoryException();

}

var objectAddress = Interlocked.Add(ref _address, size);

if (objectAddress > _limit)

{

throw new OutOfMemoryException();

}

return (nint*)(objectAddress - size);

}

Finally, we add we add methods for each type of allocation, starting with object:

public T AllocateObject<T>() where T : class

{

var mt = typeof(T).TypeHandle.Value;

var methodTable = *(MethodTable*)mt;

var ptr = ReserveMemory(methodTable.BaseSize);

// Write the header

*ptr = 0;

ptr++;

// Write the mt

*ptr = mt;

return *(T*)&ptr;

}

Then struct:

public ref T AllocateStruct<T>() where T : struct

{

var mt = typeof(T).TypeHandle.Value;

var methodTable = *(MethodTable*)mt;

var ptr = ReserveMemory(methodTable.BaseSize);

return ref Unsafe.AsRef<T>(ptr);

}

For the string there is one subtlety: the total size needs to be aligned on the pointer size.

public string AllocateString(ReadOnlySpan<char> data)

{

var mt = typeof(string).TypeHandle.Value;

var methodTable = *(MethodTable*)mt;

var size = methodTable.BaseSize + (data.Length + 1) * sizeof(char);

// Align up the size

size = (size + IntPtr.Size - 1) & ~(IntPtr.Size - 1);

var ptr = ReserveMemory(size);

// Write the header

*ptr = 0;

ptr++;

// Write the MT

*ptr = mt;

var dataPtr = (byte*)(ptr + 1);

// Write the length

*(int*)dataPtr = data.Length;

// Write the chars

var destination = new Span<char>(dataPtr + sizeof(int), data.Length + 1);

data.CopyTo(destination);

destination[^1] = '\0';

return *(string*)&ptr;

}

And finally, the array. To properly size the array, we need to know the size of its elements. We use the ComponentSize field of the method table for that:

public T[] AllocateArray<T>(int length)

{

var arrayMt = typeof(T[]).TypeHandle.Value;

var arrayMethodTable = *(MethodTable*)arrayMt;

var arraySize = arrayMethodTable.BaseSize + length * arrayMethodTable.ComponentSize;

var ptr = ReserveMemory(arraySize);

// Write the header

*ptr = 0;

ptr++;

// Write the MT

*ptr = arrayMt;

// Write the length

*(ptr + 1) = length;

return (T[])*(Array*)&ptr;

}

And our allocator is ready!

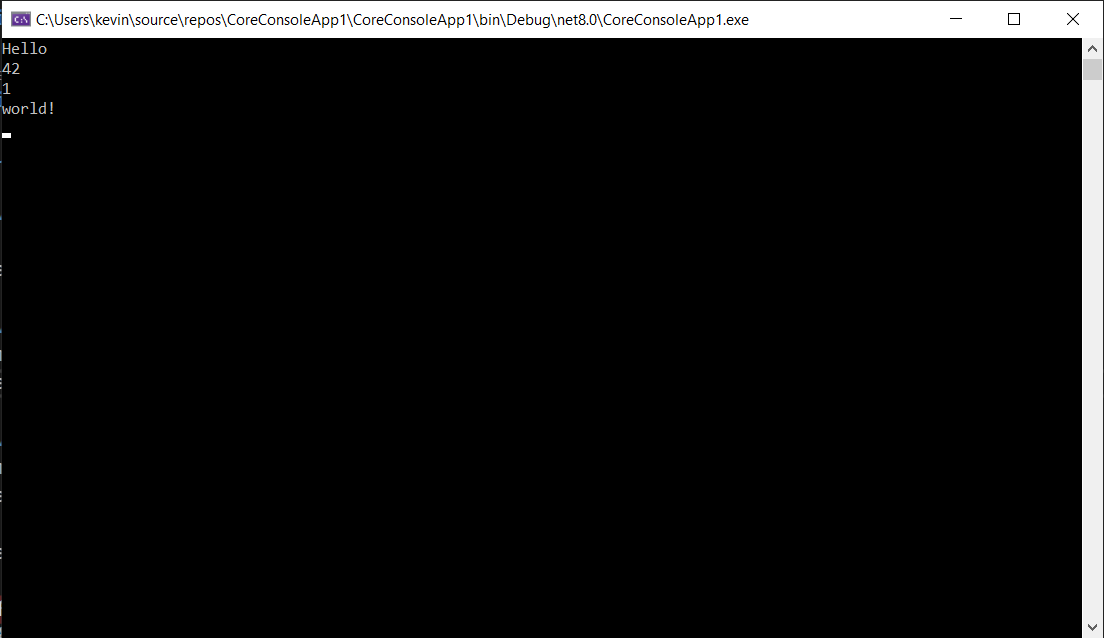

static void Main()

{

using var allocator = new BumpPointerNativeAllocator(1024 * 1024 * 100);

var array = allocator.AllocateArray<object>(4);

array[0] = allocator.AllocateString(['H', 'e', 'l', 'l', 'o']);

var myObject1 = allocator.AllocateObject<MyObject>();

myObject1.data = 42;

array[1] = myObject1;

var myObject2 = allocator.AllocateObject<MyObject>();

myObject2.data = 1;

array[2] = myObject2;

array[3] = allocator.AllocateString(['w', 'o', 'r', 'l', 'd', '!']);

foreach (var item in array)

{

if (item is string str)

{

Console.WriteLine(str);

}

else if (item is MyObject obj)

{

Console.WriteLine(obj.data);

}

}

}

Wrapping up

We have seen how to use frozen segments to store managed objects in native memory. Keep in mind that this code is not production-ready, and you shouldn’t consider using it in your applications without proper testing and benchmarking. Also, the frozen segments API is not widely used, so I wouldn’t be surprised if there were some nasty bugs lurking around. Still, it is a good excuse to have some fun and dig into the .NET type system.

If you’re interested in seeing more, we could explore in future articles how to serialize and deserialize frozen segments into files, as is already done by the FrozenObjects tool.

Addendum

After publishing this article, Egor Bogatov pointed out an issue with my allocator:

Nice! One note that _RegisterFrozenSegment isn't enough if you want an on-demand allocator - you need UpdateFrozenSegment to keep GC updated about boundaries, which is not exposed. (although, you may try to allocate a dummy object to fill the empty space in your segment) 🙂

— EgorBo (@EgorBo) January 16, 2024

In some conditions, the GC actually scans the frozen segments, just marking all the objects and then unmarking them at the end of the collection. It only happens in some precise conditions: if regions are disabled, and if the frozen segment is allocated within the GC range (the GC range being the range of memory between the lowest and the highest address of the managed heap). If the GC decide to scan our frozen segment, it will fail because it’s not filled with proper objects (since we’re allocating them one by one). There are multiple solutions to this. One is to allocate a dummy array after the last object, and set its size to the remaining space in the segment. This way, the GC will scan the dummy array and ignore the rest of the segment:

private nint* ReserveMemory(int size)

{

ObjectDisposedException.ThrowIf(_address == 0, typeof(BumpPointerNativeAllocator));

if (_address + size > _limit)

{

throw new OutOfMemoryException();

}

var objectAddress = Interlocked.Add(ref _address, size);

if (objectAddress > _limit)

{

throw new OutOfMemoryException();

}

// Allocate a dummy array at the end

var ptr = (nint*)objectAddress;

// Write the header

*ptr++ = 0;

// Write the MT

*ptr++ = typeof(byte[]).TypeHandle.Value;

// Write the length

*ptr = (nint)(_limit - objectAddress - sizeof(nint) * 2);

return (nint*)(objectAddress - size);

}

Another approach is to notify the GC of how much memory is allocated in the segment, but there is no managed API for that. We can however skip the middle-man and directly update the GC’s internal structure. Remember the IntPtr returned by _RegisterFrozenSegment? We can map it to this structure:

[StructLayout(LayoutKind.Sequential)]

public unsafe struct Heap_segment

{

public nint allocated;

public nint committed;

public nint reserved;

public nint used;

public nint mem;

During the initialization, we change its value to point to the beginning of the segment:

public BumpPointerNativeAllocator(nint size)

{

_address = (IntPtr)NativeMemory.AlignedAlloc((nuint)size, 8);

NativeMemory.Clear((void*)_address, (nuint)size);

_segment = RegisterFrozenSegment((IntPtr)_address, size);

var segment = (Heap_segment*)_segment;

segment->allocated = _address;

_limit = _address + size;

}

We can then just update the allocated field as needed (which points to the end of the allocated memory).

private nint* ReserveMemory(int size)

{

ObjectDisposedException.ThrowIf(_address == 0, typeof(BumpPointerNativeAllocator));

if (_address + size > _limit)

{

throw new OutOfMemoryException();

}

var objectAddress = Interlocked.Add(ref _address, size);

if (objectAddress > _limit)

{

throw new OutOfMemoryException();

}

// TODO: Should use Interlocked operations for thread safety

var segment = (Heap_segment*)_segment;

segment->allocated += size;

return (nint*)(objectAddress - size);

}