Investigating an InvalidProgramException from a memory dump (part 3 of 3)

In this series of articles, we’re retracing how I debugged an InvalidProgramException, caused by a bug in the Datadog profiler, from a memory dump sent by a customer.

-

Part 3: Identifying the error and fixing the bug

In the previous part, we’ve located the bad generated IL, stored in an internal CLR structure. The third part is going to be about understanding what’s wrong with the IL, and finding the root cause.

Identifying the error

There are a lot of things that can be wrong in some IL code, so I wasn’t short of stuff to try. I decided to start by checking the method size.

There are two different formats of header for IL methods: the fat header and the tiny header. A method can have a tiny header only if it doesn’t use local variables and don’t have try/catch blocks, so in my case I knew it had to be a fat header. The layout of the fat header is:

-

2 bytes: flags + size of the header (always 12 bytes)

-

2 bytes: maximum size of the stack (

maxstack) -

4 bytes: size of the method

-

4 bytes: LocalVarSig token

With that information in hand, I just had to dump 4 bytes at a 4-byte offset from the memory location of the IL:

(lldb) memory read --count 1 --size 4 --format x 0x0007fce8c983790+4

0x7fce8c983794: 0x000005fe

0x5fe means 1534 in decimal. How to check if the method body had the right size? My co-worker Tony had a bright idea: we knew that the method would finish with a ret instruction (opcode 0x2A), so I just had to look for that value at the supposed end of the method body.

I went on and dumped 1546 bytes of memory (12 bytes for the header, then the 1534 bytes for the body) to check the value of the last byte:

(lldb) memory read --count 1546 --size 1 --force --format x 0x00007fce8c983790

0x7fce8c983790: 0x1b 0x30 0x02 0x00 0xfe 0x05 0x00 0x00

0x7fce8c983798: 0x75 0x02 0x00 0x11 0x02 0x7b 0x00 0x08

[...]

0x7fce8c983d90: 0x08 0x00 0x04 0x08 0x28 0xc3 0x08 0x00

0x7fce8c983d98: 0x0a 0x2a

The method was the correct size, it was time to check the body itself. I could easily dump the raw data on the disk, but I was moderately motivated at the perspective of writing an IL parser to read it. I then realized that the dumpil command had a /i flag to print the IL from an arbitrary location:

> help dumpil

--------------------------------------------------------------------

DumpIL <Managed DynamicMethod object> |

<DynamicMethodDesc pointer> |

<MethodDesc pointer> |

/i <IL pointer>

I happily gave it a try, without much success:

> dumpil /i 0x00007fce8c983790

Incorrect argument: 0x00007fce8c983790

> dumpil -i 0x00007fce8c983790

Unknown option: -i

Since the IL was supposed to be invalid to begin with, I wasn’t really surprised that the command wouldn’t work. I decided to have a look at the source code to understand why it was failing, hoping that this would give me a clue. But it turned out that it was failing for completely unrelated reasons.

In the definition of the dumpil command, the /i option is declared, as expected:

CMDOption option[] =

{ // name, vptr, type, hasValue

{"/d", &dml, COBOOL, FALSE},

{"/i", &fILPointerDirectlySpecified, COBOOL, FALSE},

};

But then, in the argument parsing code, only - is accepted as prefix on Linux!

#ifndef FEATURE_PAL

if (ptr[0] != '-' && ptr[0] != '/') {

#else

if (ptr[0] != '-') {

#endif

For those who are not used to browsing the CLR code, FEATURE_PAL is defined when compiling for platforms other than Windows.

To summarize, dumpil is declaring a /i argument, but the parsing code looks for-i. Therefore, the command simply couldn’t work on Linux. I filled an issue, and in the meantime I compiled my own version of dotnet-dump which fixed the issue. I was finally able to use the dumpil command:

> dumpil -i 0x00007fce8c983790

IL_0000: ldarg.0

IL_0001: ldfld TOKEN 4000800

IL_0006: stloc.0

IL_0007: ldarg.0

IL_0008: ldfld TOKEN 4000803

[...]

IL_05f2: ldflda TOKEN 4000801

IL_05f7: ldloc.2

IL_05f8: call TOKEN a0008c3

IL_05fd: ret

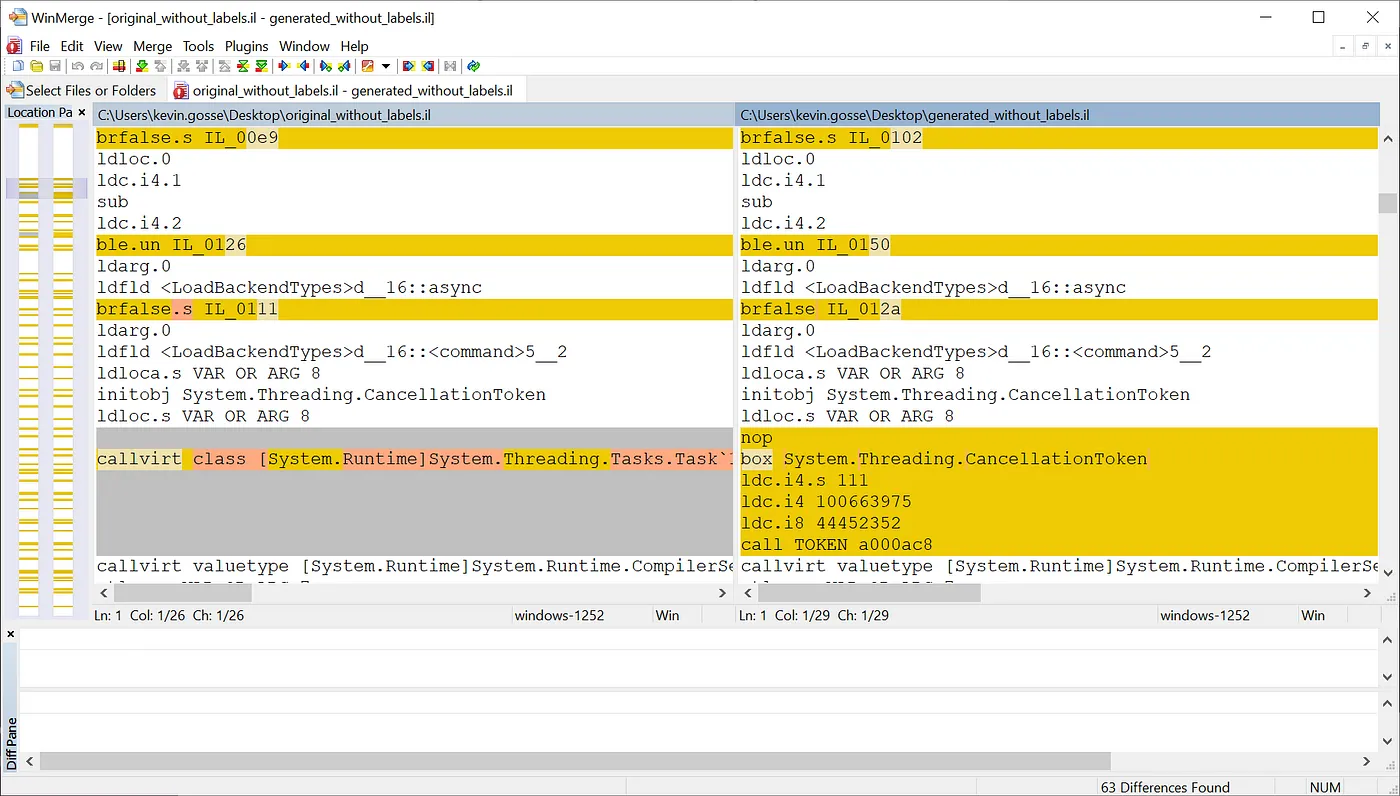

I methodically compared it with the original IL, paying special attention to the parts that we rewrote, but found nothing wrong.

Note that the method tokens are not resolved in the dumpil -i output. That’s because it doesn’t have the context of the method, so it cannot guess what module to use to resolve them (so instead of, say, call Hello::World(), it would display call TOKEN a000b60). Suspecting that the token could be wrong in the rewritten method, I tried resolving them manually. The token is named a “MemberRef token” (recognizable because it starts with a0). According to the specification, this is an index to a table that maps it to a MethodDesc (which I can then dump using the dumpmd command, as I did in previous parts of the investigation).

Quoting the ECMA specification:

II.22.25 MemberRef : 0x0A

The MemberRef table combines two sorts of references, to Methods and to Fields of a class, known as ‘MethodRef' and ‘FieldRef', respectively.

[...]

An entry is made into the MemberRef table whenever a reference is made in the CIL code to a method or field which is defined in another module or assembly.

I tried using the dumpmodule command to locate that table, but…

> dumpmodule 00007fcf13ec67d8

Name: /Npgsql.dll

Attributes: PEFile SupportsUpdateableMethods IsFileLayout

Assembly: 0000000002a3f590

BaseAddress: 00007FCF8079E000

PEFile: 0000000002A638B0

ModuleId: 00007FCF13EC7FE0

ModuleIndex: 0000000000000091

LoaderHeap: 0000000000000000

TypeDefToMethodTableMap: 00007FCF13F30020

TypeRefToMethodTableMap: 00007FCF13F31270

MethodDefToDescMap: 00007FCF13F31EE8

FieldDefToDescMap: 00007FCF13F392E0

MemberRefToDescMap: 0000000000000000

FileReferencesMap: 00007FCF13F3F740

AssemblyReferencesMap: 00007FCF13F3F748

MetaData start address: 00007FCF807DF410 (496736 bytes)

No matter what module I tried, the MemberRefToDescMapfield would always be missing. I checked the DAC implementation, and it turns out there is actually no logic to populate that field!

ModuleData->MemberRefToDescMap = NULL;

I filled an issue, then tried locating the table myself. Unfortunately, the assembly metadata is a real mess (read this article for an appetizer), so I decided to leave it as last resort and focus on other hypotheses first.

Following a suggestion from Tony, I checked the SEH table for the method. I won’t go into the details, but basically the location of the try/catch/finally blocks in a method is stored in a table at the end of the IL body. If you’re feeling playful, the structure of the table is detailed in the specification, section II.25.4.5 Method data section.

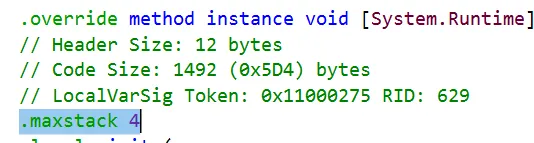

There was nothing wrong with the SEH table either, so I turned my attention to maxstack. Every method has a maxstack directive, which indicates the maximum number of items that is expected to be pushed on the stack at any given time. This information is stored on two bytes in the method header, as described in the beginning of this article.

(lldb) memory read --count 6 --size 2 --format x 0x00007fce8c983790

0x7fce8c983790: 0x301b 0x0002 0x05fe 0x0000 0x0275 0x1100

We see here that maxstack is set to 2. This is abnormally low, considering that the original method had a maxstack of 4!

This was enough to explain why the JIT would throw an InvalidProgramException. But I still had to figure out how we ended up with this value.

Fixing the bug

The IL rewriter used in the Datadog profiler is based on a sample provided by Microsoft. First, you need to be fully aware of how complex it is to rewrite IL. Let’s say we want to inject a single instruction in the middle of the method. One could think it’s just a matter of allocating a bigger buffer and inserting the new opcode. However, just doing that has a lot of impacts on the method:

-

The size of the body has changed, so the header must be updated

-

maxstackcould be impacted -

Since an instruction was inserted, all jumps destination must be recomputed

-

Same for the SEH table, delimiting the try/catch/finally blocks

-

Some instruction could need to be converted (for instance,

brfalse_sstores the jump offset on a single byte. If the additional instruction increases the offset past the maximum size, it’ll need to be converted to abrfalse) -

… and I’m probably forgetting some

Because of all those impacts, the rewriter works by disassembling the method into a tree structure, then reassembling it into bytecode after applying the changes.

Back to maxstack. By inspecting the code of the rewriter, I discovered that it doesn’t bother running a flow analysis, and instead relies on a worst-case prediction. It enumerates all the instructions in the method, and increments a value every time it sees an instruction that pushes something on the stack. That value is then assigned to maxstack. It is also never decremented when an instruction pops something from the stack.

In other words, have a look at this IL code:

IL_0000: ldarg.0 // Loads first argument on the stack

IL_0001: brtrue IL_0005 // Jumps to IL_0005 if true

IL_0002: ldc.i4 42 // Loads the value 42 on the stack

IL_0004: br IL_0008 // Jumps to the end

IL_0005: ldarg.1 // Loads the second argument on the stack

IL_0006: ldc.i4 42 // Loads the value 42 on the stack

IL_0007: add // Adds the two values

IL_0008: ret // End of the method

In C#, the method could be translated to:

public int SomeMethod(bool addValue, int value)

{

if (addValue)

{

return value + 42;

}

else

{

return 42;

}

}

If we run a flow analysis, we’ll see that either of two branches can be executed.

- If

addValueis true, then we’ll computevalue + 42. At the IL level, we use up to 2 slots on the stack:

ldarg.0 // stack = 1

brtrue IL_0005 // stack = 0

ldarg.1 // stack = 1

ldc.i4 42 // stack = 2

add // stack = 1

- If

addValueis false, then we’ll directly return42. At the IL level, we use up to 1 slot on the stack:

ldarg.0 // stack = 1

brtrue IL_0005 // stack = 0

ldc.i4 42 // stack = 1

With this flow analysis, we can conclude that maxstack should be set to 2. However, the worst-case analysis performed by the rewriter will just sum up all the instructions that update the stack, with no respect to the flow:

ldarg.0 // stack = 1

ldc.i4 42 // stack = 2

ldarg.1 // stack = 3

ldc.i4 42 // stack = 4

In this example, the rewriter concludes that maxstack should be set to 4.

This means that we grossly overestimate the value of maxstack. This could have some performance implications (surprisingly, I found no source explaining what the effects of a big maxstack would be. This could be the subject of a future article), but it shouldn’t cause any error. Plus we’ve seen that in the memory dump we end up with a value smaller than it should be (2 instead of 4), not bigger.

I then suspected an overflow, but maxstack is coded on 2 bytes, and so has a maximum value of 65535. In my tests, we computed a value of up to 350, impressive but very far from overflowing.

There was still something missing in the equation. Tony ran into this forum thread which gave us the final piece.

Remember when I explained that the IL rewriter disassembles the instructions into a tree structure? There’s a quirk to it. There are 294 IL opcodes defined, all of them with fixed size. All of them except one: switch. switch has a variable size, depending on the number of branches in the switch block. Now imagine you were defining a data structure to store those 294 opcodes. A fixed-size structure would work for all of them except one. Are you going to rethink your structure just for that one case, or find some clever trick? The original author of the IL rewriter chose the latter, and introduced a fictional opcode: switch_arg. Thanks to that, the switch block can be disassembled into a fixed-size switch instruction followed by an arbitrary number of switch_arg instructions. Then everything is stitched back together when re-assembling the method.

How does that impact us? As I mentioned before, to compute maxstack, the rewriter uses a table that associates instructions to their effect on the stack. That table is defined as an array, mapping the index of the opcode to a value (1 or 0). That value is used to increment maxstack:

void AdjustState(ILInstr * pNewInstr)

{

m_maxStack += k_rgnStackPushes[pNewInstr->m_opcode];

}

k_rgnStackPushes is the table. AdjustState is called for every IL instruction in the method.

The k_rgnStackPushes array is automatically populated from the opcode.def file provided by Microsoft (see the “stack behavior” columns), using some macros. See the problem yet? Since switch_arg is a fictional opcode, it is not defined in the official list provided by Microsoft, and the IL rewriter author forgot to take that into account. We end up with a table of 294 elements, but we manipulate 295 different opcodes. Whenever we try to increment maxstack for the 295th opcode, we read a value outside of the array and all bets are off.

This is fine most of the time: it means that the maxstack value that we compute is complete garbage, but we always overestimate it… Unless the garbage value is big enough to cause an overflow.

I wanted that ultimate confirmation of what was happening, so I decided to check the memory dump to see what was the value just outside of the array.

To do so, I started by locating the array in our symbols:

$ nm -C Datadog.Trace.ClrProfiler.Native.so | grep k_rgnStackPushes

0000000000472e60 d k_rgnStackPushes

Then I used LLDB to get the base address of the module:

(lldb) image dump sections Datadog.Trace.ClrProfiler.Native.so

Sections for '/opt/datadog/Datadog.Trace.ClrProfiler.Native.so' (x86_64):

SectID Type Load Address Perm File Off. File Size Flags Section Name

---------- ---------------- --------------------------------------- ---- ---------- ---------- ---------- ----------------------------

0xffffffffffffffff container [0x00007fcf8629c000-0x00007fcf864fc3cd) r-x 0x00000000 0x002603cd 0x00000000 Datadog.Trace.ClrProfiler.Native.so.PT_LOAD[0]

[...]

This told me that the module was mapped at the address 0x00007fcf8629c000. I then added the offset of the array found in the symbols to compute the final address: 0x00007fcf8629c000 + 0x472e60 = 0x7fcf8670ee60

I dumped a few bytes to be sure, and as expected found a sequence of 0 and 1:

(lldb) memory read --count 4 --size 4 --format x 0x7fcf8670ee60

0x7fcf8670ee60: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000001 0x00000001

I then dumped 295 elements to find the garbage value:

(lldb) memory read --count 295 --size 4 --force --format x 0x7fcf8670ee60

0x7fcf8670ee60: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000001 0x00000001

[...]

0x7fcf8670f2e0: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

0x7fcf8670f2f0: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x866fe7a0

0x866fe7a0! That was more than enough to overflow the 2-bytes maxstack.

After identifying the issue, the fix was disappointingly simple. We just had to add the missing value to the k_rgnStackPushes array.

… A two lines patch to conclude one week of investigation.

Wrapping things up

That investigation was a good reminder of some key debugging principles I learned through the years:

-

Debugging is a creative process. Every problem is unique, you won’t find step-by-step instructions to debug your exact case. This means you’ll often get stuck, expect it and don’t lose hope.

-

If your debugging tools don’t have a command to get that you need, it doesn’t mean you have to give up. There are probably other means to get the information you seek, as long as you’re not afraid of digging into the lower layers of abstraction.

-

When you’re out of ideas, find a coworker and explain your understanding of the situation. It’s very likely that they’ll come with a different angle, giving you new things to try.