Writing a .NET profiler in C# - Part 5

In the previous parts of the series, we built the foundation we needed to write a .NET profiler in C#. If you missed them, you can find them here:

- Part 1: wrapping a managed object into a fake COM object to use the profiling API.

- Part 2: refined the solution to use instance methods instead of static methods.

- Part 3: automated the process using a source generator.

- Part 4: how to invoke methods from a native COM object.

Since then, I extracted the source generators into a dedicated library, named NativeObjects. Feel free to use it for your own projects! I then used NativeObjects to build Silhouette.

Silhouette

Silhouette is a library that wraps the profiling APIs, and provides a few helpers to make it easier to write a .NET profiler in C#. It’s still a work in progress, but a large part of the profiler API is already covered. You can find the package on Nuget and the source code on GitHub. We’re going to use it to build a simple CPU profiler.

Writing a simple CPU profiler: initial setup

First, we need to create a new C# project and enable NativeAOT. This is done by editing the csproj file and adding the following:

<PropertyGroup>

<PublishAot>true</PublishAot>

</PropertyGroup>

Then, we need to add a reference to Silhouette:

<ItemGroup>

<PackageReference Include="Silhouette" Version="1.0.0" />

</ItemGroup>

To bootstrap the profiler, we need to write a class that inherits from Silhouette.CorProfilerCallbackXxBase (replace xx by the maximum version of ICorProfilerCallback you want to target). We then override the Initialize method, which will automatically be called with the highest version of ICorProfilerInfo supported by the runtime.

internal class CorProfiler : CorProfilerCallback11Base

{

protected override HResult Initialize(int iCorProfilerInfoVersion)

{

throw new NotImplementedException();

}

}

Then, we need to export a DllGetClassObject method that will be called by .NET to create an instance of our profiler. The method is expected to return an instance of IClassFactory, that itself will be used to create the instance of ICorProfilerCallback. Silhouette provides a helper to make this easier:

internal class DllMain

{

private static Silhouette.ClassFactory? _instance;

[UnmanagedCallersOnly(EntryPoint = "DllGetClassObject")]

public static unsafe HResult DllGetClassObject(Guid* rclsid, Guid* riid, nint* ppv)

{

// TODO: replace with your own guid

if (*rclsid != new Guid("0A96F866-D763-4099-8E4E-ED1801BE9FBC"))

{

return HResult.E_NOINTERFACE;

}

_instance = new Silhouette.ClassFactory(new CorProfiler());

*ppv = _instance.IClassFactory;

return HResult.S_OK;

}

}

Although it’s not mandatory, it is strongly recommended to validate the guid passed in the rlcsid argument to validate that the user meant to load your profiler. The guid that you receive is the one that is set in the CORECLR_PROFILER environment variable.

Now we can go back to our CorProfiler.Initialize method. We need to do three things:

- Validate the version of

ICorProfilerInfothat we received. In our case, we want to make sure the runtime supports at least version 10. - Use

ICorProfilerInfo.SetEventMaskto enable the profiling features that we will need. - Do any other initialization that we need.

To call ICorProfilerInfo methods, we can use the relevant ICorProfilerInfoXx property. It’s the responsibility of the developer to not call a method that is not supported by the runtime (for instance, if iCorProfilerInfoVersion is 10, don’t try to use the ICorProfilerInfo11 property or bad things will happen).

For our profiler, we’re going to enable COR_PRF_ENABLE_STACK_SNAPSHOT to be able to use the ICorProfilerInfo2::DoStackSnapshot method, and COR_PRF_MONITOR_THREADS to be notified of the creation of new threads. We also create a timer that will be used to periodically print the stack traces of all the threads.

internal class CorProfiler : CorProfilerCallback11Base

{

private Timer? _timer;

protected override HResult Initialize(int iCorProfilerInfoVersion)

{

if (iCorProfilerInfoVersion < 10)

{

return HResult.E_FAIL;

}

var result = ICorProfilerInfo.SetEventMask(COR_PRF_MONITOR.COR_PRF_ENABLE_STACK_SNAPSHOT | COR_PRF_MONITOR.COR_PRF_MONITOR_THREADS);

if (result)

{

_timer = new Timer(OnTick, null, 0, 2000);

}

return result;

}

}

Listing the threads

To collect the stacktraces of all threads, we need to know what threads are running. One way to do that is to use ICorProfilerInfo4::EnumThreads to enumerate all threads. However, I have yet to write the proper helpers in Silhouette to use native enumerators, so we’re going to use a different approach. We’re going to listen to the ICorProfilerCallback::ThreadAssignedToOSThread and ICorProfilerCallback::ThreadDestroyed events to keep track of the threads.

To listen to a ICorProfilerCallback event, we simply need to override the corresponding method on our CorProfiler class. We then add or remove the ThreadId from a ConcurrentDictionary that will be used to keep track of the threads.

private readonly ConcurrentDictionary<ThreadId, int> _threads = new();

protected override HResult ThreadAssignedToOSThread(ThreadId managedThreadId, int osThreadId)

{

_threads[managedThreadId] = osThreadId;

return HResult.S_OK;

}

protected override HResult ThreadDestroyed(ThreadId threadId)

{

_threads.TryRemove(threadId, out _);

return HResult.S_OK;

}

Walking the stack

To walk the stack of a thread, we’re going to use the ICorProfilerInfo2::DoStackSnapshot method. The target thread needs to be suspended first. Normally, to minimize the impact of the profiler, we would suspend the threads one by one, walking their stack and resuming them as quickly as possible. However, this is much more challenging than it sounds. If we were to call SuspendThread, the thread would be suspended at an arbitrary location, which could lead to deadlocks if for instance it holds an allocator lock.

Instead, we’re going to use the ICorProfilerInfo10::SuspendRuntime method to suspend all the managed threads. It uses the same mechanism as the GC to suspend the threads at a safe location so it prevents deadlocks. This approach has major downsides: it’s much slower (we’re suspending all threads even though we’ll only walk one at a time), and it skews the results (because the threads are only suspended at safe points). However, those drawbacks are acceptable for our simple profiler.

private unsafe void OnTick(object? _)

{

var result = ICorProfilerInfo10.SuspendRuntime();

if (!result)

{

return;

}

foreach (var (threadId, osThreadId) in _threads)

{

// TODO: walk the stack

}

_ = ICorProfilerInfo10.ResumeRuntime();

}

DoStackSnapshot takes a ThreadId and a callback. The callback is called synchronously for each frame of the stack. It also has a clientData argument that we can use to pass any data we need to the callback. Usually you would try to avoid allocating memory in the callback (because of the deadlock issue mentioned before), so you would need to preallocate a buffer and pass it as clientData. We don’t have this problem thanks to SuspendRuntime, but we’re still going to simulate what it would look like.

First, we declare our buffer structure. We have to pick a size so we make it big enough to store up to 1024 frames (this is a purely arbitrary number, stacktraces can in theory be bigger but this should be enough to cover most cases):

private struct StackWalkContext

{

public const int MaxFrames = 1024;

public FramesArray Frames;

public int Count;

[InlineArray(MaxFrames)]

public struct FramesArray

{

private nint _frames;

}

}

We then declare the callback that will be called by DoStackSnapshot. Because it’s invoked from native code, we must decorate it with the UnmanagedCallersOnly attribute.

[UnmanagedCallersOnly(CallConvs = [typeof(CallConvStdcall)])]

private static unsafe HResult WalkThread(FunctionId funcId, nint ip, COR_PRF_FRAME_INFO frameInfo, uint contextSize, byte* context, void* clientData)

{

// Retrieve the buffer by ref to avoid making a copy

ref StackWalkContext stackWalkContext = ref *(StackWalkContext*)clientData;

if (stackWalkContext.Count >= StackWalkContext.MaxFrames)

{

// The stacktrace is bigger than 1024 frames, stop walking

return HResult.E_ABORT;

}

stackWalkContext.Frames[stackWalkContext.Count++] = ip;

return HResult.S_OK;

}

Then we just have to call DoStackSnapshot with the appropriate arguments. We can declare our buffer on the stack without pinning it because the callback is called synchronously:

private unsafe void OnTick(object? _)

{

var result = ICorProfilerInfo10.SuspendRuntime();

if (!result)

{

return;

}

StackWalkContext context = default;

foreach (var (threadId, osThreadId) in _threads)

{

context.Count = 0;

result = ICorProfilerInfo2.DoStackSnapshot(threadId, &WalkThread, COR_PRF_SNAPSHOT_INFO.COR_PRF_SNAPSHOT_DEFAULT, &context, null, 0);

if (!result)

{

Console.WriteLine($"[Profiler] Stackwalk failed for thread {osThreadId}: {result}");

continue;

}

// TODO: Resolve symbols

}

_ = ICorProfilerInfo10.ResumeRuntime();

}

Resolving symbols

The stacktrace we collected is a list of instruction pointers. To make it useful, we need to resolve those pointers to function names. For each of those instruction pointers, we need to:

- Call

ICorProfilerInfo2::GetFunctionFromIPto get theFunctionIdof the function. - Call

ICorProfilerInfo::GetFunctionInfoto get theModuleIdand the function’s metadata token from theFunctionId. - Call

ICorProfilerInfo::GetModuleMetaDatato retrieve an instance ofIMetaDataImportfor the module. - Call

IMetaDataImport::GetMethodPropsto get the name of the method and the owner type metadata token (mdTypeDef) from the function’s metadata token. - Finally, call

IMetaDataImport::GetTypeDefPropsto get the name of the type from the owner type metadata token.

In C++, this gets very verbose very quickly because each method returns the value as out parameters, and you have to check the return code at each step. Silhouette makes it much simpler by wrapping all the return values into a single HResult<T>. It can be deconstructed into a (HResult error, T result) if you want to manually check the error code, or you can use the ThrowIfFailed() method to throw an exception if the error code is not S_OK. For ICorProfilerInfo::GetModuleMetadata, Silhouette also wraps the result into a ComPtr<T> wrapper that implements IDisposable and takes care of the proper AddRef/Release calls.

So for instance this C++ code:

ClassID classId;

ModuleID moduleId;

mdToken token;

HRESULT hr = info->GetFunctionFromIP(ip, &classId, &moduleId, &token);

if (FAILED(hr))

{

return hr;

}

Becomes either:

var (hr, functionInfo) = ICorProfilerInfo.GetFunctionFromIP(ip);

if (!hr)

{

return hr;

}

Or:

try

{

var functionInfo = ICorProfilerInfo.GetFunctionFromIP(ip).ThrowIfFailed();

}

catch (Win32Exception)

{

// ...

}

We can now put everything together and write a ResolveMethodName method that will resolve the name of a method from an instruction pointer:

private string ResolveMethodName(nint ip)

{

try

{

var functionId = ICorProfilerInfo.GetFunctionFromIP(ip).ThrowIfFailed();

var functionInfo = ICorProfilerInfo.GetFunctionInfo(functionId).ThrowIfFailed();

using var metaDataImport = ICorProfilerInfo.GetModuleMetaData(functionInfo.ModuleId, CorOpenFlags.ofRead, KnownGuids.IMetaDataImport).ThrowIfFailed().Wrap();

var methodProperties = metaDataImport.Value.GetMethodProps(new MdMethodDef(functionInfo.Token)).ThrowIfFailed();

var typeDefProps = metaDataImport.Value.GetTypeDefProps(methodProperties.Class).ThrowIfFailed();

return $"{typeDefProps.TypeName}.{methodProperties.Name}";

}

catch (Win32Exception)

{

return "<unknown>";

}

}

And then call it from our OnTick method:

private unsafe void OnTick(object? _)

{

var result = ICorProfilerInfo10.SuspendRuntime();

if (!result)

{

return;

}

StackWalkContext context = default;

foreach (var (threadId, osThreadId) in _threads)

{

context.Count = 0;

result = ICorProfilerInfo2.DoStackSnapshot(threadId, &WalkThread, COR_PRF_SNAPSHOT_INFO.COR_PRF_SNAPSHOT_DEFAULT, &context, null, 0);

if (!result)

{

Console.WriteLine($"[Profiler] Stackwalk failed for thread {osThreadId}: {result}");

continue;

}

Console.WriteLine($"[Profiler] Thread {osThreadId}:");

for (int i = 0; i < context.Count; i++)

{

var ip = context.Frames[i];

string name = ResolveMethodName(ip);

Console.WriteLine($"[Profiler] - {name}");

}

}

_ = ICorProfilerInfo10.ResumeRuntime();

}

Of course, in a real-world scenario, you wouldn’t display the results directly in the console. You would probably aggregate them over a period of time into a file, and use a separate application to read them.

Testing the profiler

To test the profiler, we can write a simple console application:

namespace TestApp;

internal class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

var threads = new Thread[]

{

new Thread(Method1) { IsBackground = true },

new Thread(Method2) { IsBackground = true },

new Thread(Method3) { IsBackground = true },

new Thread(Method4) { IsBackground = true },

new Thread(Method5) { IsBackground = true }

};

foreach (var thread in threads)

{

thread.Start();

}

Console.WriteLine("Hello, World!");

Console.ReadLine();

}

static void Method1()

{

Thread.Sleep(Timeout.Infinite);

}

static void Method2()

{

Thread.Sleep(Timeout.Infinite);

}

static void Method3()

{

Thread.Sleep(Timeout.Infinite);

}

static void Method4()

{

Thread.Sleep(Timeout.Infinite);

}

static void Method5()

{

Thread.Sleep(Timeout.Infinite);

}

}

To attach the profiler, we need to start the app with the appropriate environment variables:

@set CORECLR_ENABLE_PROFILING=1

@set CORECLR_PROFILER={0A96F866-D763-4099-8E4E-ED1801BE9FBC}

@set CORECLR_PROFILER_PATH=CpuProfiler.dll

@TestApp.exe

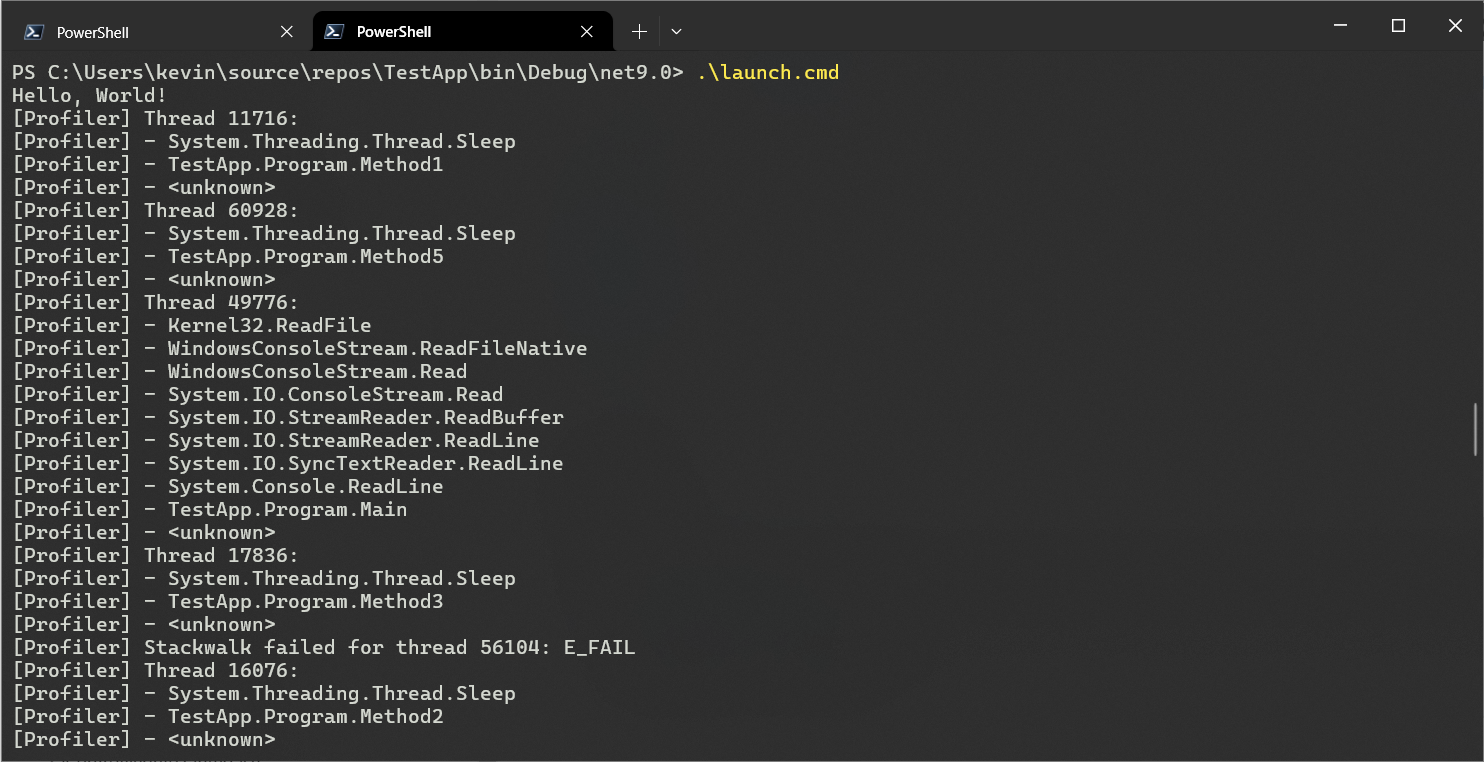

And we can see the stacktraces of all the managed threads:

Conclusion

We’ve seen how to use Silhouette to write a simple CPU profiler in C#. Of course, an actual profiler would be much more complex, but I hope to lower the barrier to entry for anyone interested in writing one. While you would probably want to use C++ for a performance-critical profiler, C# can be an interesting alternative for a profiler that doesn’t require the lowest possible footprint (for instance, to collect code-coverage from unit tests).

The code used in this article is available on GitHub.